story, images, and illustrations by Evelyn Dyer

Maine experienced above-average rainfall this summer, which kept the days cooler than usual. While this may have stifled some vacation plans from visitors, it made for some fantastic days working in Acadia National Park, where the fungi are thriving.

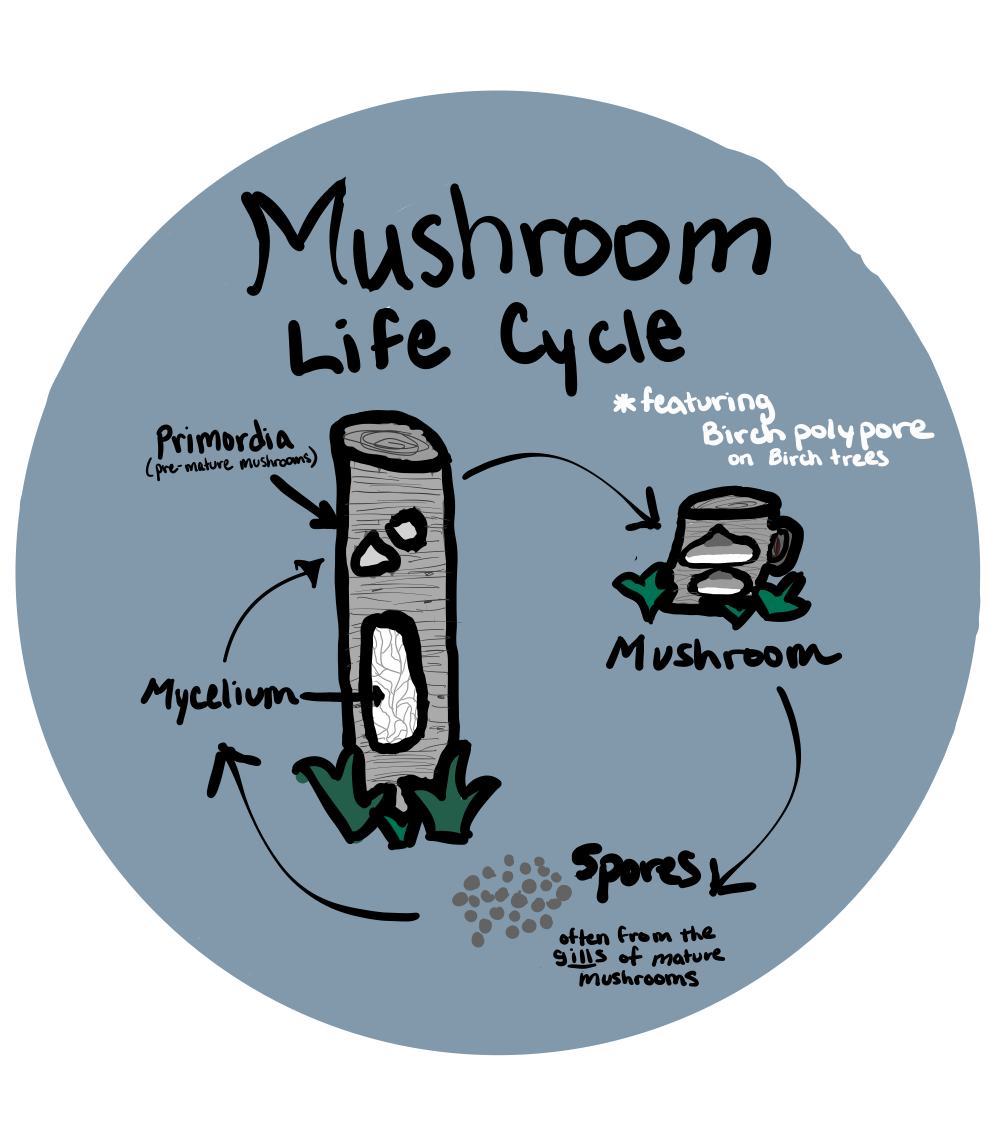

Fungi are a large group of organisms that includes molds, yeasts, mildews, rusts, smuts, and mushrooms. The wet, cooler temperatures made it the perfect time for mushrooms to pop up from their hiding spots within logs, soil, leaves, and other decaying matter from the mycelium (the main body of the fungi). Mushrooms are simply the fruiting body of the fungi (mycelium) that lives within other matter and are charged with the task of spreading the spores. It’s easiest to think of mushrooms as apples to a tree; mushrooms are the fruit to the mycelium.

In June, Dr. Richard Morrison led Schoodic Institute’s ecology technicians on a fungi scavenger hunt. Richard is a micromycologist (tiny fungi scientist) from the Northwest by training, and is now a macro-mycologist (big fungi scientist) in his free time.

Our walk down the Hemlock Trail was eye-opening. Around every corner Richard was discovering new fungi on the trail, while we all struggled to see just one. I had to train my eyes to search for things I normally would overlook. I scoured the forest floor and trees for a mushroom. Soon the colorful fungi came into focus. While I could appreciate the diversity mushrooms brought to the landscape, I found it hard to connect with something so small unless I knew what it was. Much like knowing someone’s name, we needed to meet and greet the fungi, so we got a crash course on fungi identification.

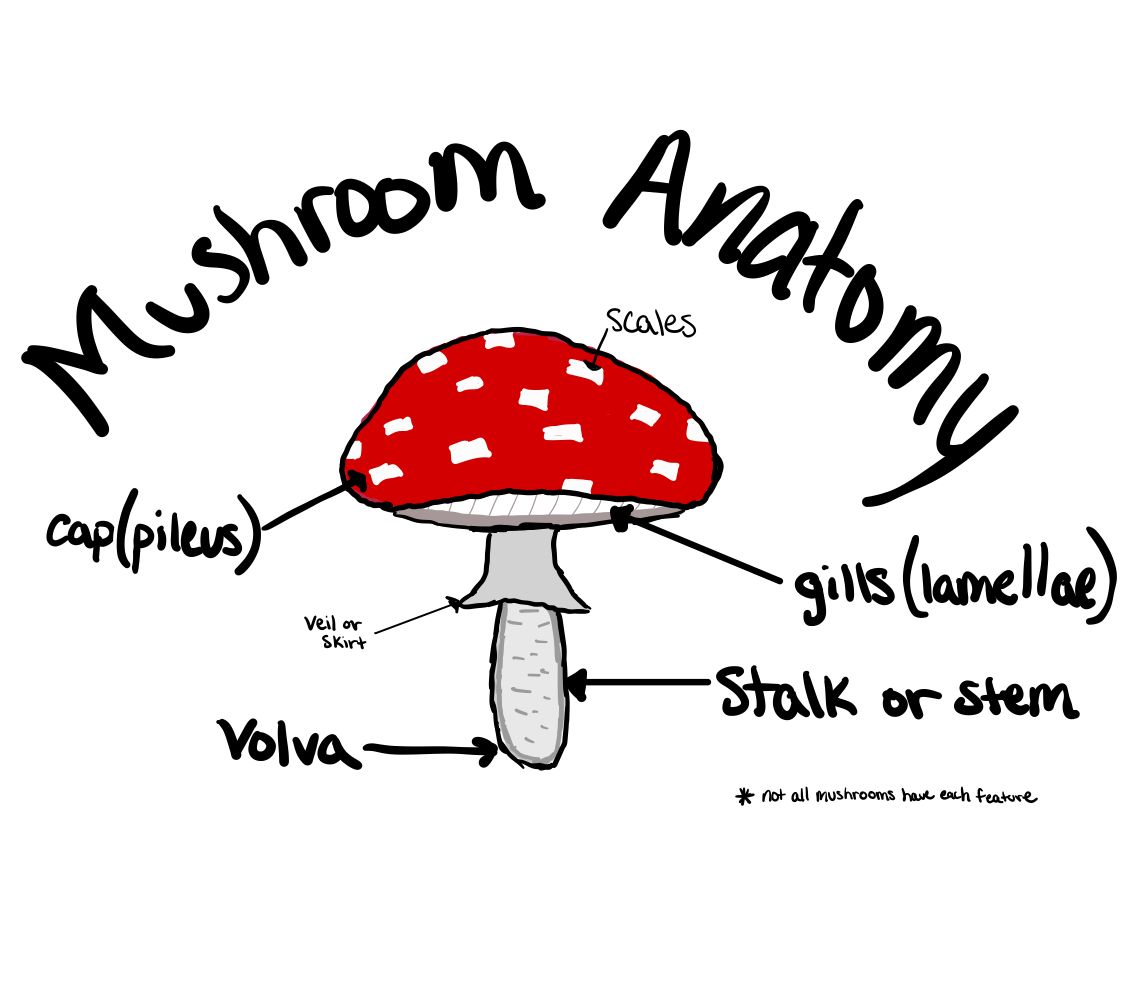

While the task seemed daunting, Richard assured us that anyone can participate in identifying fungi. The key is to gather as much information on them as possible – it’s a labor of love. When possible, take notes! Remember to mark the location where the mushroom or fungi was found. For mushrooms in particular, there are a few characteristics that are important to note; however, there is a lot of variability in the fungi kingdom so this next part is only for mushrooms. Any photographs should highlight the most important areas of the mushroom: the cap, gills, stalk or stem, and the volva.

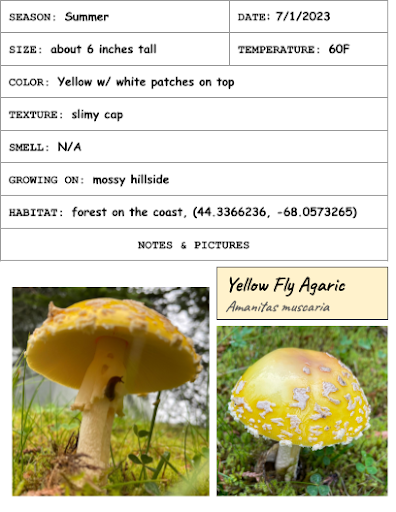

Here’s an example of some notes about a Fly Agaric I found on the Schoodic Institute campus:

The Fly Agaric I found also featured a skirt that was at one point attached to the rest of the cap forming a veil, to protect the young mushroom’s gills. Once it reaches maturity that veil drops to look like a skirt on the stalk. The reason I didn’t show a picture of the volva here is because collecting mushrooms (foraging) is not permitted when on Acadia National Park lands. It’s also important to refrain from harvesting any young mushrooms for identification because they have not matured enough to release the spores that help the fungi reproduce.

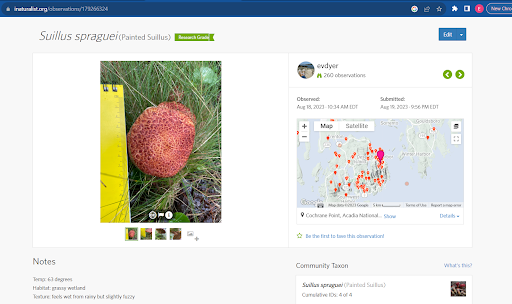

We shared our observations on the iNaturalist platform. For fungi, in addition to the standard data of image, date, and location, it is helpful to add notes about identifying features like the cap, gills, stem, texture, color, and odor. There are some mushrooms that don’t even follow the most common anatomy like Witch’s Butter or a Coral Fungi, so try to describe to the best extent possible!

iNaturalist will be your best friend because you also get a faster response time than if you were to try and search for the answers yourself in a mushroom field guide. Just remember to upload your location and include as much descriptive detail on the specific mushroom as possible including up to four photos (enough to capture the identifying features and surrounding habitat). Here’s an example of a Painted Suillus Mushroom from the Great Meadow:

By using iNaturalist it is possible to contribute “research grade” observations. This means the data are validated and can be used by researchers or park staff interested in fungi or biodiversity.

Fungi play many roles in the ecosystem. They are decomposers, which are extremely important for nutrient circulation. Without the fungi decomposers, nutrients would take a longer time to reach the soils and thus be less accessible to other organisms. Some fungi are also part of mycorrhizal relationships with trees, and can show something about the intricacies and health of the surrounding ecosystem.

This season, I led 7 out of 10 Schoodic Institute bioblitzes at the Great Meadow in Acadia National Park. We identified more than 50 different fungi or lichen species over the past five months! So, I must say thank you to Dr. Richard Morrison for opening my eyes to the beautiful world of fungi, and I encourage everyone to get out there and explore their local ecosystems because you may just find something that piques your interest, too.