by Chris Nadeau, Climate Change Adaptation Scientist

I was astonished the first time I visited Cadillac Mountain, but not just by the outstanding views. I felt like I was transported to the top of one of the high elevation peaks in New Hampshire, Vermont, or New York. But at only 1,530 feet, Cadillac Mountain is thousands of feet shorter. Nonetheless, the bare rock, gnarled old trees (called krummholtz), and other low-lying vegetation on Acadia’s mountain summits makes me feel like I am above 4,000 feet in the subalpine zone of mountain ranges farther west. Exposure to extreme winds, ice, snow, and cold temperatures hurling in from the Atlantic ocean are the primary factors making Acadia’s summits so much like high elevation mountains to the west.

Similar vegetation types, regardless of elevation, means that mountains throughout the northeastern United States face similar threats and management challenges. Like Acadia’s summits, many summits in the region are degraded from human trampling, which causes soil and vegetation loss, and need to be restored. These same mountains are also highly vulnerable to warmer temperatures and heavier rain events resulting from climate change. Protecting, restoring, and increasing the resilience of these unique ecosystems will require cooperative learning among the many different management agencies and user groups throughout the Northeast. However, few forums exist for natural resource managers and summit users to share knowledge about summit management and conservation. In fact, many summit conservation groups work in isolation.

Schoodic Institute, in partnership with the Appalachian Mountain Club, recently hosted a workshop on summit management at the Forest Ecosystem Monitoring Cooperative Conference in Burlington, Vermont. The workshop was attended by a lively group of approximately 32 people, from 3 states, and a diversity of organizations and job types (note, not all people completed the surveys presented below).

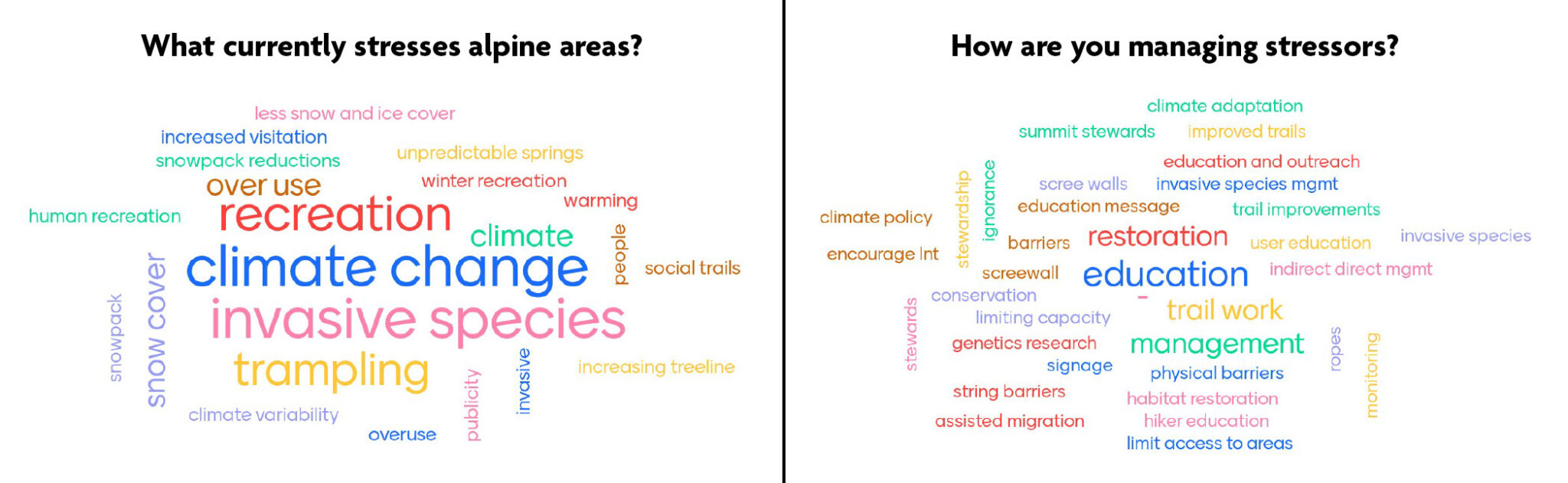

The group identified climate change, invasive species, and impacts from recreation as the primary current stressors on summits. Acadia’s summits face all these threats, although invasive species are less of a problem here, in part because of careful management by the National Park Service. There are many current efforts throughout the region to minimize impacts from these stressors, but the most common themes included education, recreation management, and restoration/trail work. Schoodic Institute, Friends of Acadia, and the National Park Service are working to research and improve all three types of management, and we could therefore learn from other efforts throughout the Northeast.

The group identified climate change, invasive species, and impacts from recreation as the primary current stressors on summits. Acadia’s summits face all these threats, although invasive species are less of a problem here, in part because of careful management by the National Park Service. There are many current efforts throughout the region to minimize impacts from these stressors, but the most common themes included education, recreation management, and restoration/trail work. Schoodic Institute, Friends of Acadia, and the National Park Service are working to research and improve all three types of management, and we could therefore learn from other efforts throughout the Northeast.

In the future, the group expects the current major stressors (i.e., climate change, invasive species, and recreational impacts) to get worse. For example, reduced snowpack due to climate change could result in higher vegetation and soil impacts from winter recreation. Education, recreation management, and restoration/trail work were common management ideas for these future stressors. However, it was also recognized that we might need to modify these management approaches to meet new challenges. For example, many summits in the Northeast have a summer program of educators on summits, similar to Friends of Acadia’s Summit Stewards Program at Acadia, to help minimize visitor impacts. However, there is no winter programming to educate winter recreationists. Moreover, winter recreationists might be a different audience than summer recreationists, and therefore require different messaging and engagement strategies for education.

In the future, the group expects the current major stressors (i.e., climate change, invasive species, and recreational impacts) to get worse. For example, reduced snowpack due to climate change could result in higher vegetation and soil impacts from winter recreation. Education, recreation management, and restoration/trail work were common management ideas for these future stressors. However, it was also recognized that we might need to modify these management approaches to meet new challenges. For example, many summits in the Northeast have a summer program of educators on summits, similar to Friends of Acadia’s Summit Stewards Program at Acadia, to help minimize visitor impacts. However, there is no winter programming to educate winter recreationists. Moreover, winter recreationists might be a different audience than summer recreationists, and therefore require different messaging and engagement strategies for education.

The group also identified some new future stressors, such as upward expansion of some mammals that could impact plant communities, decreases in the population size and distribution of plants and animals from warming, or soil warming that could affect the soil microbiome and ultimately reduce primary production. These future stressors pose unique challenges for management. For example, conserving populations of some plants could require banking seeds or augmenting populations with warm-adapted seeds or seedlings from other locations. However, some in the group also recognized that novel management approaches, such as augmenting populations, are controversial because they could have unintended consequences. In Acadia, Schoodic Institute is leading the way in testing these novel management approaches to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks of unintended consequences.

The group identified a series of recommendations that could help address current and future management challenges at Acadia and beyond, including:

- An archive of relevant reports and papers on alpine ecology and stewardship, and a summary of the existing research.

- A regular venue for practitioners and academics to meet to discuss alpine ecology and stewardship. The Waterman Fund hosts the Northeast Alpine Stewardship Gathering approximately every other year, but meetings in off years would be extremely useful.

- Coordinated monitoring of key aspects of alpine ecology, such as plant genetics and the soil microbiome.

- Institutionalized stewardship that moves away from volunteer education staff.

Schoodic Institute, in partnership with the Appalachian Mountain Club, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Forest Service, is pursuing resources to act on these recommendations, which could help conserve our beautiful mountain summits in Acadia and throughout the Northeast.

This summer at Acadia, we learned that a community approach to conservation can have a big impact. Through the Save Our Summits event – organized by Friends of Acadia, Schoodic Institute, and the National Park Service – over 200 hundred volunteers carried 3750 pounds of soil to the summits of Sargent and Penobscot Mountains. Schoodic Institute and the National Park Service used that soil to restore 29 degraded areas on the two summits. Imagine the impact we could have if the great northeastern summit community worked together to conserve our mountain summits. That’s the vision we have, and the recent workshop was the first step in achieving that vision.