By Catherine Schmitt, Science Communication Specialist

To find these creatures, to study their habits and organization, to consider the wonderful order of nature, leads through delightful paths into the realms of science…the simple observation of the curious objects which lie at one’s feet as one walks along the beach is a delightful pastime. – Augusta Foote Arnold, 1901

Science is of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true. – Joseph Henry, 1856

A major goal of ecology is to understand what explains the presence, absence, and abundance of any given species, to answer questions such as: Why does the Acadia shoreline look the way it does, all crowded with barnacles, mussels, periwinkles, rockweed? How do species become established and survive? How connected are they to nearby populations? This question of connectivity is especially relevant for marine species.

To be an intertidal organism is to be born in the water, to spend early life riding ocean currents, sometimes for hundreds of miles, until finally drifting back to shore and settling down. Mussels, barnacles, common periwinkle, green crabs, and rockweed can all be found from Maine to Massachusetts, but in different arrangements. In the south, mussels and barnacles are abundant. In the north, seaweed tends to dominate. In between lies Acadia National Park, where communities don’t follow either of these patterns, and where Catherine Matassa of University of Connecticut is trying to understand what explains why who is where and when.

Her research, conducted with colleagues at Northeastern University and funded by the National Science Foundation, examines whether regional differences in intertidal communities are influenced by large-scale factors like temperature, food availability, and nearshore currents that affect population size and connectivity. She calls this “macroecology.”

Matassa is continuing a long tradition of marine science in Acadia.

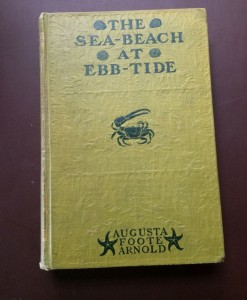

Before ecology, there was natural history, with a widespread attempt in the 19th century to inventory and classify every marine organism living in a place. Lots of everyday people contributed, collecting shells and pressing seaweed. Because marine animals of the far north could be found in the eastern Gulf of Maine but nowhere else in America, the Acadia region attracted prominent scientists. They combed the shoreline and dredged the sea floor in search of new species, beginning in 1843 with Jesse Wedgwood Mighels and Captain Green Walden, to William Stimpson, Alpheus Hyatt, Alpheus Packard, and Addison Emery Verill, students of Louis Agassiz in the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Verrill and Packard continued to work in the region through the 1870s. They had assistance in identifying their specimens from Smithsonian collaborators Mary Rathbun and Harriett Richardson. These same two women are acknowledged in The Sea-Beach at Ebb-Tide by Augusta Foote Arnold.

Published in 1901, the 600-page book was a comprehensive, scientifically accurate field guide to marine life. But unlike previous publications, which appeared as articles in scientific journals and technical reports, Sea-Beach was richly illustrated and written for a wide audience, with chapters on “Distribution of Animal Life in the Sea,” “Classification,” and “Some Botanical Facts about Algae.” There was also a chapter on “Collecting at Bar Harbor,” which is clearly drawn from the author’s own experience of Mount Desert Island tidepools. “Here is an immense natural aquarium,” she wrote, “full of living wonders.”

There is little published information about Augusta’s adult life or her connection to Mount Desert Island. She married Francis Arnold in 1869; they had three children; they lived in New York City. They stayed at the Porcupine Hotel in Bar Harbor in 1892, which may have been when she did her tidepool research. She was an author, writing The Century Cook Book in 1895 and Luncheons: A Cook’s Picture Book in 1902 (both under the name Mary Ronald). Somehow, in between these two books, she finished Sea-Beach and used her real name.

She was so bold! But then again, her mother was a scientist and women’s rights activist. Growing up in Seneca Falls, New York, Augusta was four years old when Eunice Newton Foote signed (and edited) the Seneca Falls Convention’s Declaration of Sentiments (We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal…)

Augusta’s father signed, too. So did their next-door neighbor, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

After the convention, Eunice turned her attention to science. Did young Augusta watch her mother’s experiments, marvel at the way light sparkled in the glass cylinders of air set outside to capture the warm rays of the sun? Eunice’s results, “Circumstances affecting the heat of sun’s rays” were presented at the tenth annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, but not by her, because women were not allowed to speak. In presenting Eunice Foote’s research, Joseph Henry acknowledged the injustice of such policy, which echoed the sentiment declared at Seneca Falls, He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself.

Eunice Foote was the first person to define the greenhouse effect. Her daughter was the first person to write about the tideline using language that anyone could understand.

For the scientific details, Arnold had help from other Smithsonian scientists, and botany professors, herbaria curators, and librarians near her home on West 78th Street. Her husband, Francis Arnold, heir to the New York Coffee Exchange, was a member of the New York Botanical Garden. She had access to the elite circle, took their knowledge and illustrations, and turned them into the first guide to intertidal life available to a wide audience. Other women were writing popular field guides, too, keeping alive the common interest in natural history as the professionalization of science enclosed it within male-dominated institutions and associations.

The Sea-Beach at Ebb-Tide sold 1,741 copies in the first five months, and it remained relevant for decades after Augusta’s death in 1904. Ed Ricketts had a copy, so did Rachel Carson.

“Anyone who works in the intertidal is keenly observant, curious, and not afraid to get wet,” said Hannah Webber, Marine Ecology Program Director at Schoodic Institute. “When I think about Catherine Matassa’s work, or that of Susan Brawley, Jessie Muhlin, and Branwen Williams – we’re all looking at patterns and trying to understand what causes those patterns. And it’s never just one thing.”

From Sea-Beach: “The first objects on the rocky beach to attract attention are the barnacles and rockweeds. They are conspicuous in their profusion, the former incrusting the rocks with their white shells, and the latter forming large beds of vegetation; yet both are likely to be passed by with indifference because of their plentifulness. They are, however, not only interesting in themselves, but associated with them are many organisms which are easily overlooked. The littoral zone is so crowded with life that there is a constant struggle for existence,— even for standing-room, it may be said,— and no class of animals has undisputed possession of any place.”

Ecologists would take up these associations in the twentieth century, including Jane Lubchenco, former Adminstrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, focusing on small-scale processes like competition, predation, and disturbance, because they could be manipulated in an experimental setting. But there wasn’t a lot of agreement in their results. Something bigger was going on.

Arnold hinted at these larger influences in her chapter on Bar Harbor. “The rocky coast harbors the boreal fauna and flora which depend upon such physical conditions, and the shores at Bar Harbor are typical of those found elsewhere in northern New England. The rocks give shelter from the beating surf, while life has exposure to the cold, pure waters of the arctic current.”

In the semi-enclosed sea that is the Gulf of Maine, water circulates counter-clockwise. The cold Eastern Maine Coastal Current brushes the Schoodic Peninsula, then veers offshore at Isle au Haut. To the south and west, the current is warmer, mixed with water from large rivers and stirred up by summer winds. One of the questions Catherine Matassa is trying to determine whether the currents create a barrier to larval dispersal, with eastern Maine intertidal animals descending from local parents, while southwestern areas draw from more distant source populations.

Four sites in Acadia are among her 20 field sites from Boston to Eastport. She collects and counts settling larvae and uses field experiments to test the effects of temperature, disturbance, and predation by whelks and periwinkles on the settlers. “How do large-scale processes, like ocean currents, waves, and population connectivity, interact with smaller-scale processes, like predation or thermal stress on individuals, to generate the different patterns of species abundance seen throughout the Gulf of Maine?” she asks. “For example, crabs and snails have plenty of mussels and barnacles to eat in the southern Gulf of Maine, but limited recruitment of these species in the north means that crabs and snails have to come up with other dining options. What’s exciting about Acadia is it sits in the middle of these two extremes, and what happens here might help us understand why we see differences in the dominant species north and south.”

“It’s exciting to think about and work on natural patterns at different scales, and to find connection between the small and large scales,” said Webber. “When I am looking at how rockweed affects barnacle settlement, I need to do that in the context of Matassa’s work. And when I am looking at how the presence of rockweed affects intertidal temperatures it has to be framed within temperatures experienced in the larger context—the whole rim of the Gulf of Maine.”

Matassa is collaborating with park resource managers, sharing her findings about the intertidal zone, said Acadia National Park science coordinator Abraham Miller-Rushing. “Her research will help us anticipate and respond to the changing environment, and is the type of research we need more of,” he said. “And her work is also plain old inspiring, just like the past work it builds on.”

Augusta Foote Arnold wrote in 1901, “Animals of the sea are united into organic associations comprising millions of individuals inseparably connected and many of them interdependent.” Today, scientists like Catherine Matassa and Hannah Webber continue to observe and study these connections, considering the wonderful order of nature, embracing the true.

Thanks to Sarah Schmitt for assisting with research for this article at the New York Public Library.