The History and Importance of Inventory and Monitoring in the National Parks

by Lucy Enders

Since 1992, the National Park Service Division of Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) has been providing scientific natural resource inventories and long-term monitoring for parks within the National Park System. The overarching goal of the program is to monitor park “vital signs” in order to track changes in ecosystem health.

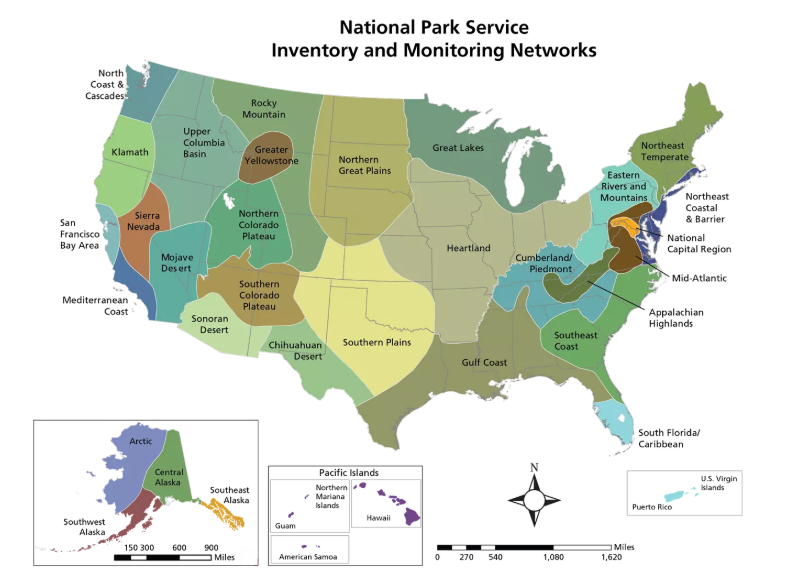

Before the program was established–and later mandated by Congress–park managers had no organized way to access information regarding the plants, animals, and other natural resources within their parks. The I&M program went through several iterations but ultimately took on a “network” structure, creating 32 Inventory and Monitoring networks across the country.

Splitting the participating parks into networks made sense for several reasons. It created standardized procedures for collecting data in entire regions, resulting in a decreased chance of informational gaps. Consequently, each network has the flexibility to prioritize data important to their specific region–perhaps the Gulf Coast Network wouldn’t need to monitor snow chemistry, but the Rocky Mountain Network does! Similarly, the Rocky Mountain Network wouldn’t prioritize amphibian monitoring the same way as the Gulf Coast Network, which hosts especially dense amphibian diversity. The network structure also guarantees research for smaller, often capacity- thin parks within the system. Rather than leaving it up to each individual parks’ natural resource division, which takes a lot of money and staff, I&M is able to collect that data and create reports that can be easily interpreted by park staff.

I’m a forest health monitoring technician with Schoodic Institute, charged with monitoring forest health plots for I&M. I only spend one day of our field season on the Schoodic Peninsula. The rest of the time I am traveling, visiting parks of the Northeast Temperate (NETN), Mid-Atlantic (MIDN), and Northeast Coastal and Barrier (NCBN) Networks, a total of 19 parks.

The I&M program addresses the need for current and relevant data to inform management decisions in an incredibly efficient way. One of the key applications when it comes to forest health is the tracking of invasive plants, pests, and pathogens. Through consistent inventories, we are able to identify new arrivals of potentially problematic species, and act quickly to address them. Additionally, since we are surveying across such a large region, I&M data can be used alongside similar monitoring programs, to learn about trends in invasive species presence. One example of an emerging pathogen we have been identifying is beech leaf disease (BLD). BLD severely impacts native beech trees and has no known cure, though several treatments are being tested. It has been found in many of our parks, and every year we detect new areas affected. Having records of where the disease is occurring is the first step in being able to manage it and save such an important forest canopy species.

Had the I&M program not been implemented, we may never have realized the full extent of the peril that faces eastern forests. Through collaboration between parks and monitoring networks across the region, park scientists were able to compile incredibly strong evidence showing that many park forests are unsustainable as they are. It was through this that the Resilient Forests Initiative was created as a regional movement to promote active management to address this crisis. The initiative has already been hugely successful in getting approval for projects including invasive plant management, native tree planting, and controlling overbrowsing by white-tailed deer. And this is just one example of what can be accomplished when continual and collaborative research throughout the National Park System is prioritized. The goal has always been for this science to be ongoing. The most wonderful part of I&M, in my opinion, is that it was created to exist in perpetuity. It’s an excellent approach to conducting research within the National Park System, ensuring that we can preserve our country’s most precious places for the enjoyment of future generations. Organizations like Schoodic Institute help to keep that research moving along!

Banner photo by Catherine Schmitt