Humans outperform Merlin Sound ID in point-count surveys

by Brooke Goodman

Merlin Bird ID is a popular smartphone application that identifies birds based on their songs. You probably have heard of Merlin or maybe even used it yourself to identify some birds you were hearing. Ornithologists have been using tools like this, based on ever-growing libraries of recorded bird sounds, to learn more about bird populations for years. Since 2021, when the Cornell Lab of Ornithology made this technology widely accessible to anyone with a smartphone, Merlin has revolutionized human interaction with the avian world.

However, the human ear is still better at detecting birds, especially when they are far away. Merlin can’t fully replace human listeners and observers, but could act as an aid to improve point-count surveys, according to the results of a study we recently published in the journal Ornithological Applications.

For scientists, Merlin presents a potential solution to perpetual problems in bird point counts. Point counts are the most common way scientists survey birds and consist of a human keeping track of every bird they hear or see within a certain amount of time (often 10 minutes) at one location. Experienced surveyors are hard to find, expensive to hire, and can have huge variation in their abilities. Passive acoustic monitoring techniques address some of these issues, but come with their own costs and complications. So, we wondered if Merlin could help minimize these problems by functioning as a no-cost, in-field listener with consistent performance.

However, before integrating Merlin into scientific research, the performance of Merlin and humans must be quantitatively compared. “Merlin is not perfect; you may have experienced it confusing one bird species for another, or even calling a red squirrel a hairy woodpecker. But, identifications by humans are also far from perfect, and a formal comparison could reveal the strengths and weaknesses of the two methods,” said Schoodic Institute senior bird engagement specialist Seth Benz.

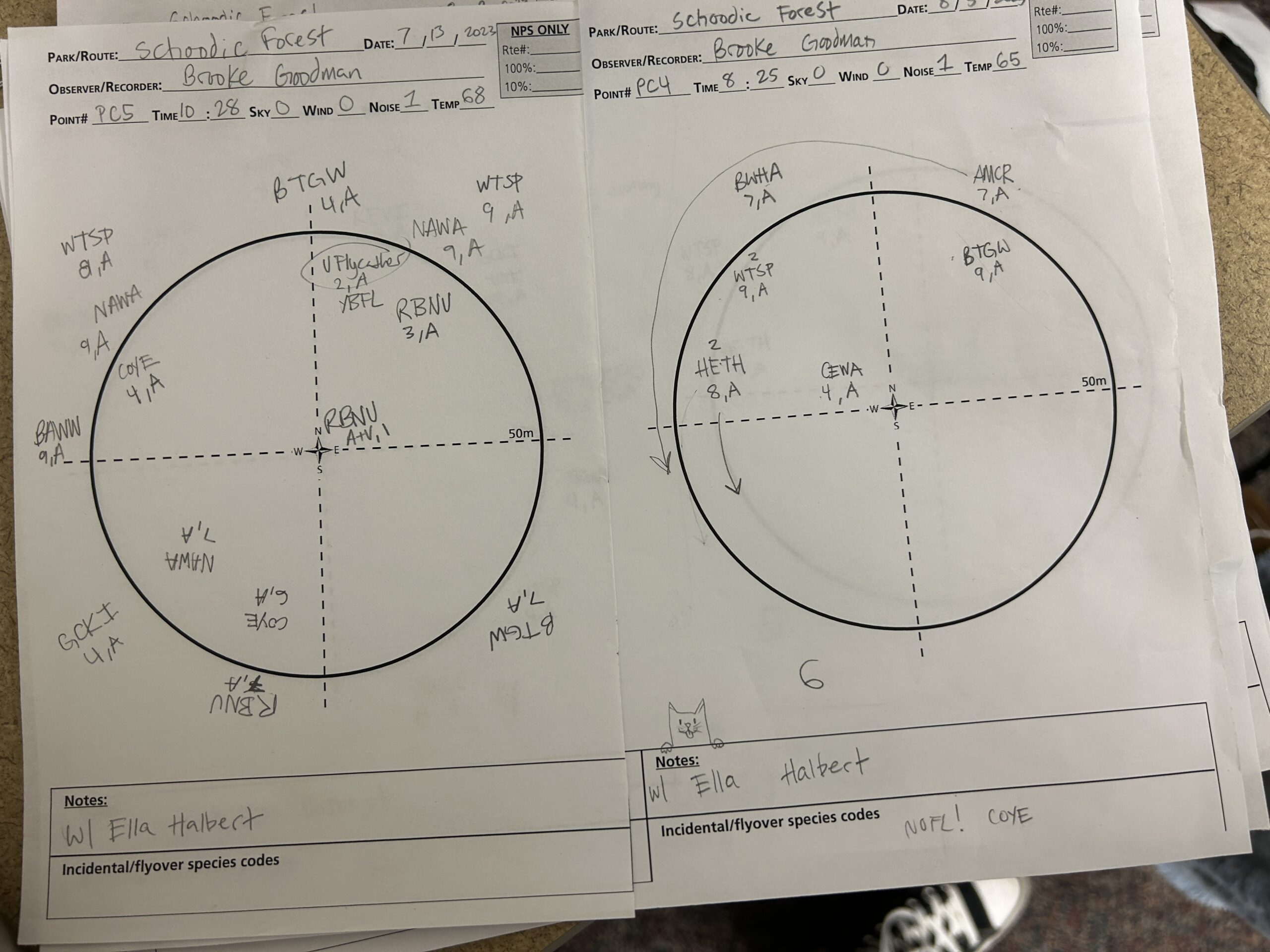

In 2023, as the Cathy and Jim Gero Acadia Early-Career Fellow in Science Research, working with colleagues at Schoodic Institute and University of Pittsburgh, I set out to conduct this comparison through 144 paired human and Merlin point counts in Maine Coast Heritage Trust’s Schoodic Forest preserve. Our goals were to evaluate differences between humans and Merlin through the species identified, the number of individual detections, and overall precision.

The biggest difference found between humans and Merlin was the number of individual detections throughout the course of the study. If a bird was present, a human was 72 percent more likely to detect it. Merlin detected 12 false positive species over the course of the study; these were species that, despite being reported by Merlin, were not truly present. There were four species that Merlin identified correctly that humans missed, and eight species that were only ever identified correctly by humans.

“Considering these results, we propose Merlin not as a replacement for human surveyors, but as an aid to increase detection probability and accuracy,” said Schoodic Institute data analyst and co-author Kyle Lima.

With humans acting as primary observers and listeners, Merlin can act as a second listener, with humans arbitrating disagreements between devices and evaluating possible false positives when needed. We concluded that surveys using Merlin need to test inter-device variability just like they would inter-observer variability, and keep in mind that identification will vary for different species and at different levels of background noise. Merlin generated different species lists for 57 percent of point counts when running on two different devices at the same time, perhaps due to differences in microphone quality or device positioning.

Merlin isn’t perfect, but neither are humans. With further research into this methodology, technology like Merlin could help address some of the challenges associated with point-count based research.

Related paper: Humans outperform Merlin Sound ID in field-based point-count surveys by Brooke D. Goodman, Kyle A. Lima, Seth Benz, Nicholas A. Fisichelli, and Justin Kitzes. Ornithological Applications.