by Jackie Florman, 2019 Intern, Colby College

The morning light had just begun to dust our campsite with a hazy, brown-orange glow. We unzipped our tents and emerged, 4:15 a.m., no coffee for us. The campground was asleep, save for our boot-clad trio. We loaded big, orange buckets of field gear into the car: Blowtorch. Granola bars. Knitting needles. Rock drill. Extra drill bits. Check, check, check; all of our fieldwork essentials were loaded up and ready to go for an early morning in the intertidal zone. The car crawled down the narrow, dirt road of our campground, quietly and slowly so as not to wake up the other campers.

We were racing the tide. Low tide was at 5:12 a.m., and we only had two hours after dead low tide to get our work done. If we didn’t finish, we would have to wait until the evening low tide, so time was of the essence.

It was one of the last monitoring sites to install along the coast of Maine, part of Hannah Webber’s research project that spans almost the entire coast, and the northernmost study site, a few miles from the U.S.-Canada border. The landscape was flat, forest-coated, expansive.

Hannah drove and Sally and I used the atlas and a set of GPS photographs to navigate to the site. Cobscook Bay came into view as we turned down an unpaved road, our destination bathed in reflective orange and milky pink from the rising sun.

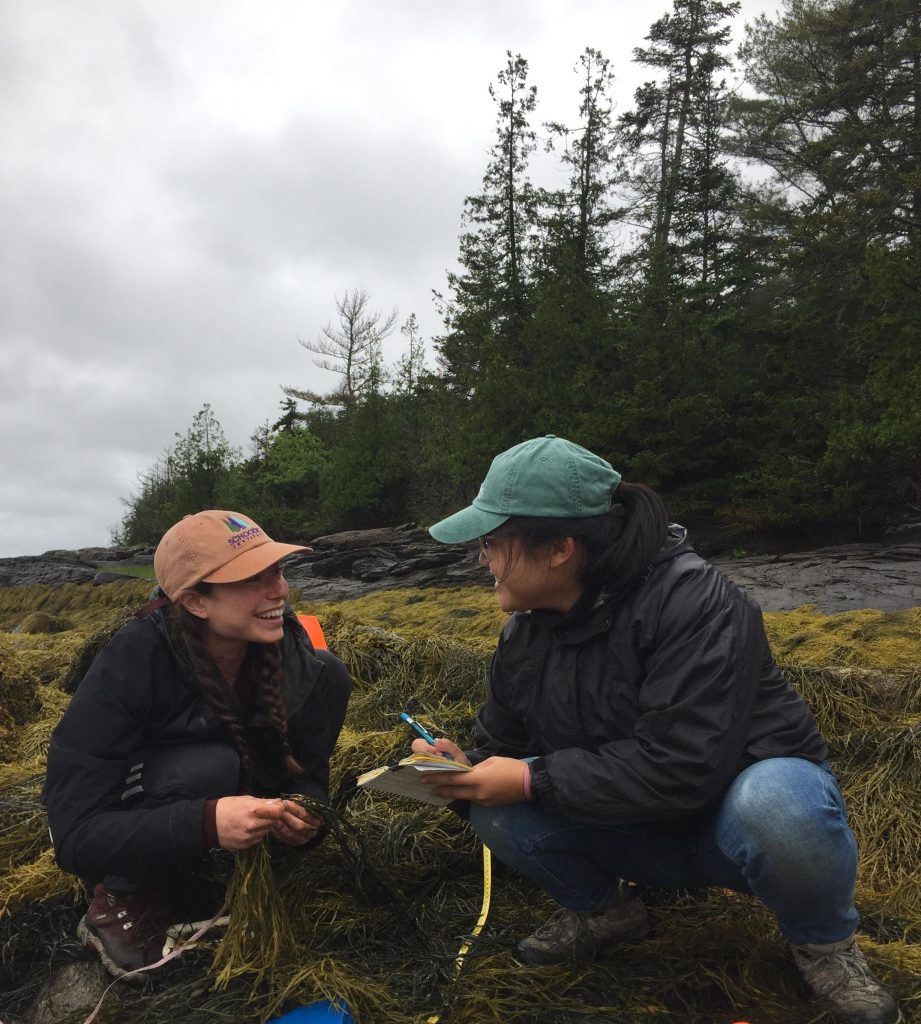

We hopped out of the car, each grabbing a large and cumbersome vessel filled with field gear. Hannah led us down an old, overgrown ATV trail and across an enormous field of rockweed, comparing what we saw before us to the printed satellite photographs of the site we had reviewed earlier.

We picked a relatively flat location and lay down two bisecting transect tapes, oriented in the cardinal directions to form an invisible circle, the study site. We put sponges underneath the rockweed, which would help us measure how much water the algae holds under it when the intertidal zone is exposed to air as opposed to water.

We stuck knitting needles with measuring tapes secured to them into the rockweed forest to measure how deep the bed of algae is at each point along the transect tapes. We drilled bolts into the rocks so Hannah and her team could come back later to observe and photograph how the intertidal ecosystem changed after rockweed was harvested.

The clouds moved in, slowly at first, and then at a rapidly-increasing pace. The tide, too, had begun to trickle in. I watched the earth transform into water. Liquid flowed in from either direction: the salt of the sea blending with the freshwater of the sky. We stood between the two.

We were drenched within minutes, clinging trekking pants and squelching socks. We were just mapping the site as the rain’s pace escalated and the tide water pooled beneath our feet. Finally, we were driven out. We packed up the gear and marched a mile or so up through the mud, deep and sticky, to the car. Hannah offered to bring our drenched field clothing to a nearby laundromat. Sally and I took her up on the offer.

We drove away as the storm moved along the coast in a blur of grey and black, grumbling across Cobscook Bay, saturating the air with thick droplets of mid-summer storm water. We were dripping wet and knew that we’d have to return to the site that evening, at the next low tide, but I didn’t mind. Another day in the field, I thought, grinning to myself. Another day in the field.