by Catherine Schmitt

Tree pests and diseases present a serious and growing threat to forests across national parks. From fungi that are causing rapid death of ohi’a, “the most important tree in Hawaii” in Hawaii Volcanoes, to pine and spruce beetles in Rocky Mountain and hemlock woolly adelgid in Shenandoah, the problems caused by these invasive species are only getting worse as increasing global trade and travel accelerate their spread.

Forests in the eastern United States have already experienced multiple transformations as towering chestnut trees succumbed to blight and elms died as invasive beetles spread disease. Such pests are a grave concern for managers at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park in Vermont, who tend Mount Tom Forest, one of the oldest planned and continuously managed forests in the United States.

Beech bark disease and gypsy moth are already present and having significant impact on the park’s forest. A changing climate may bring even more pests as those that are cold-sensitive, such as red pine scale and hemlock woolly adelgid, expand their range as winters get warmer.

Tree pests can impair both the nature of the forest (the trees) and its historic character, challenging the park’s mandate to preserve the forest and continue progressive stewardship. National Park Service Ecologist Kyle Jones worked with Schoodic Institute Ecology Technician Diana Gurvich and President & CEO Nicholas Fisichelli to assess how susceptible the forest might be to different pests.

“Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller tells the evolving story of forest stewardship in America,” said Fisichelli. “In their forward-looking management, they have identified several stressors, including tree pests and climate change, as needing further assessment to inform management decisions. In 2014, I worked with the U.S. Forest Service to produce a forest vulnerability to climate change assessment for Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller, and we hosted a workshop at the park. The park has had more assessments and studies since then, and was looking for guidance on emerging forest pests and the potential management options.”

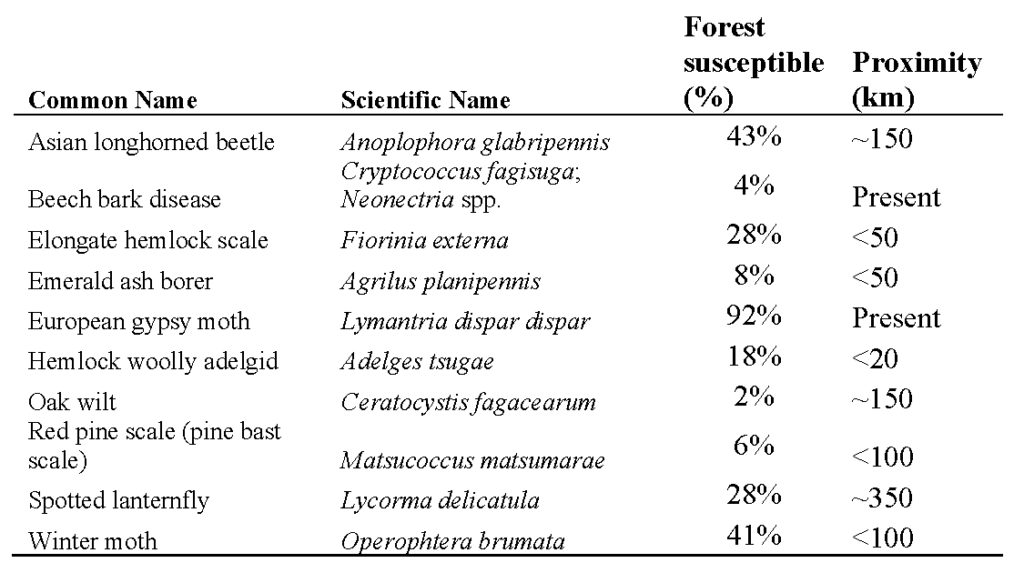

Focusing on the 10 species of insects and pathogens with potential for greatest impact on the park (and creating detailed profiles for each), Gurvich and Fisichelli estimated arrival dates and the susceptibility of different stands of trees, using monitoring data from the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service.

Gypsy moth, Asian longhorned beetle, and winter moth threaten the greatest area of forest, because they affect multiple tree species. All of the most common overstory trees in the park are at risk, with red maple, sugar maple, black cherry, and northern red oak affected by the most pests. But a more important factor than the total number of pest species in estimating impact is how fast they spread.

Pests may arrive on their own or be moved inadvertently by people across the landscape. A recent review estimated that Eastern U.S. forest pests are expanding their ranges at an average rate of about 5 kilometers (or 3 miles) per year, though this varies among species and years. Regardless, at this pace all but one of the species studied will have arrived in Mount Tom Forest by the year 2050. Spotted lanternfly, currently the farthest away from the park, only arrives if the rate of spread accelerates to 20 kilometers per year. If range expansion is slowed, managers can expect only hemlock woolly adelgid in the next thirty years.

Many tree pests, such as beech bark disease and gypsy moth, have already been present at Mount Tom for a long time and have caused damage. The number of pests is, unfortunately, likely to rise in the future, challenging the ability of managers to foster healthy forests. Preparing for the inevitable arrival of these pests and keeping up-to-date with emerging management options is critical, according to Gurvich and Fisichelli.

Because forest management is part of the mission of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller, managers there can implement a wider array of options than most other parks typically use to deal with forest pests. They can trim, cut, remove, and plant trees to reduce the frequency of outbreak occurrence and minimize severity of outbreaks.

But Gurvich was surprised that there aren’t more options available. “I was expecting to be able to create a more detailed suite of management options, especially for pests that have been around for a long time,” said Gurvich. “It’s possible other options exist and I just couldn’t access them in the scientific literature, which I see as a huge barrier for managers trying to stay up to date with the research.”

Whatever actions staff at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller take to address invasive forest pests, they are likely to share them with forest managers at other parks and protected areas, continuing the legacy of human relations with the forested landscape.

Read the full report, Non-native Tree Pest Assessment for Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park.

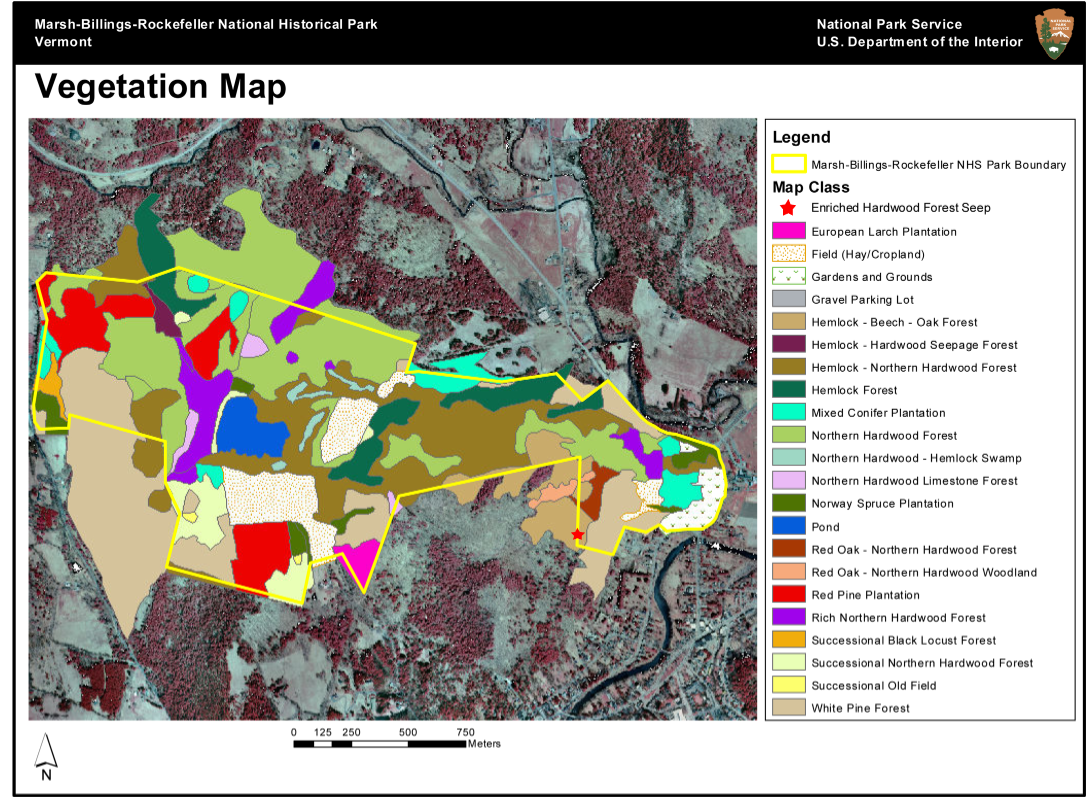

Below is a vegetation map of the Mount Tom Forest showing stands of different tree species: