story and photos by Shannon O’Brien, 2021 Ecology Technician

With the sound of retreating tides, the smell of salt spray, and the view of Mount Desert Island to the west, I found myself back in the intertidal zone of the Schoodic Peninsula conducting research once again this year. The scenery remains the same but the work has changed. A seasonal staff of two technicians a year ago grew to a crew of eight intrepid technicians and interns. With a diverse array of skills and more projects to be worked on, this summer was far more eventful than last year. One project that got more attention was the inquiry into Jonah crabs’ late summer migration to the shores of Schoodic.

Last year, the monitoring efforts consisted of walking along a stretch of shoreline, finding crabs, and recording data. This year the goal was to initiate a mark-recapture protocol for the Jonahs. In early summer, interns Jessica Moskowitz and Elizabeth Halasz were tasked with testing experimental marking techniques. These experiments aimed to find out what marking method would work best for longevity in marine environments and could also easily be carried out in the field. The method that had the best potential for success proved to be using paint pens in conjunction with gluing numbered dots to each crab.

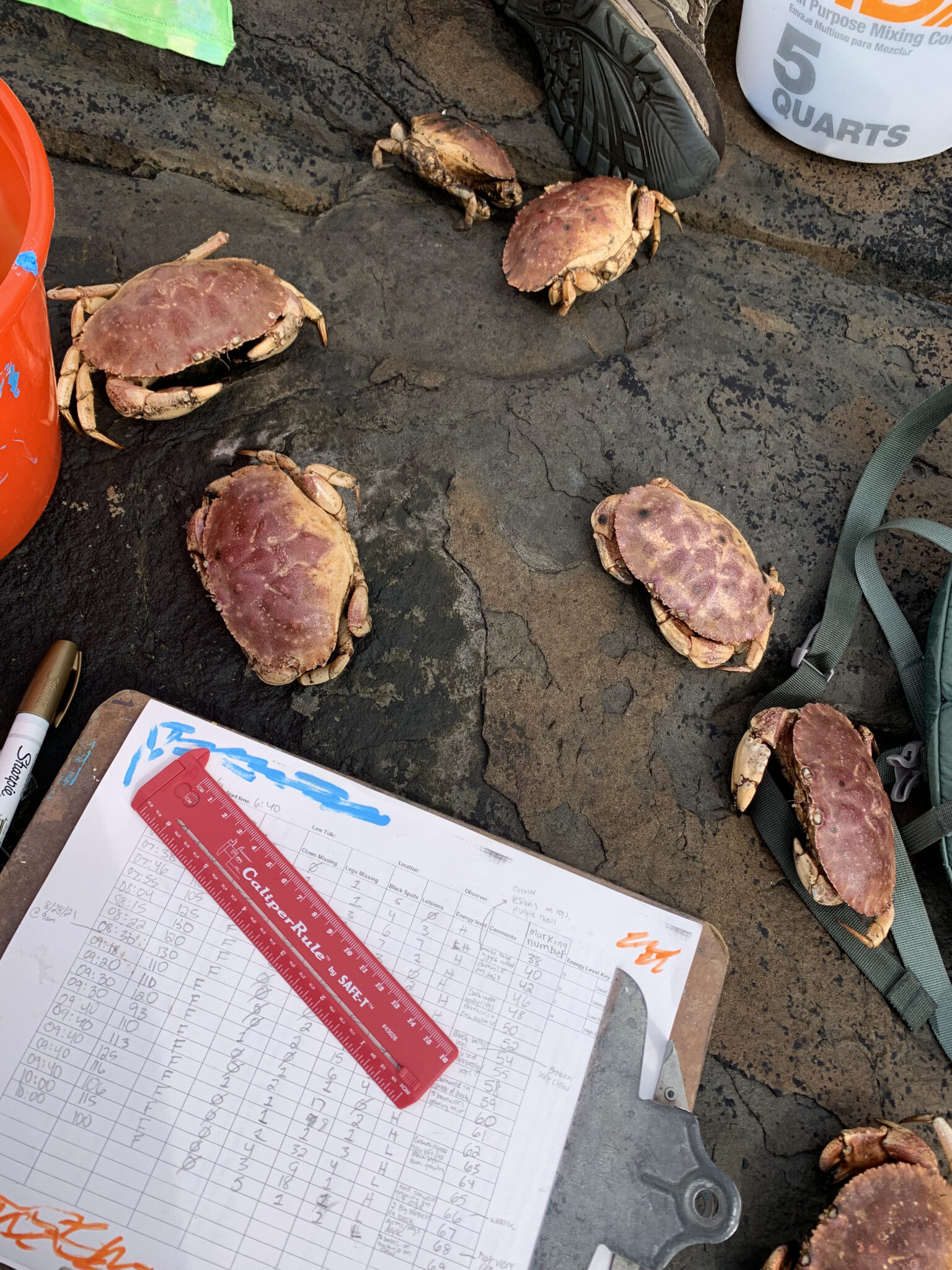

With a new way to learn about crab behavior, a rotating cast of technicians took to the intertidal to find and mark crabs. The first Jonahs were observed in mid-July. With the tides in mind, we would gear up: orange buckets with rags, glue, nail polish, paint pens, a toothbrush, and a ruler. Donning high visibility vests, waterproof shoes, and a spare layer for those chilly mornings, we walked down the Sundew Trail to our site.

Scanning for crabs along the intertidal and giving the crabs a free ride in the buckets proved easy enough; the more complicated task was settling down on a rock and marking each crab found. The marking process seemed straightforward: dry each crab, wipe away marine grime, paint a number on the left side of the face; and glue a dot of paper with the same number on the right of the face.

While the markings dried, we recorded data about each crab’s condition. The number of claws or legs missing, sex, presence of black spots or lesions, and the overall energy level were noted. With a swipe of clear nail polish to fortify the paper dot and a line of gold paint on the back, we would carefully place the crabs under tufts of seaweed to give them time to readjust after our disturbance.

Moving along our usual path, this process was repeated multiple times throughout the summer. By the end of the crab season in September, we had visited the same site 11 times and marked a total of 101 Jonah crabs. In comparison, last year we made six site visits and surveyed a total of 236 crabs. The difference is due to the time it took to survey each crab. On one visit, technician Emily Jackson and I were able to mark 10 crabs before running out of time for the day. We still traversed our usual route and were able to see 60 more crabs. That was atypical for a field day as the average marked crab per site visit was 11.

As for the recapture, we unfortunately did not re-encounter any marked crab. This outcome is not surprising. Little is known about the seasonal migration of Jonahs to shore, and without more thorough research it is difficult to implement monitoring efforts. Short of becoming the epicenter of crab research, Schoodic Institute can make some changes to better monitor the crustaceans. Further experimentation of marking techniques in combination with more frequent visits to the site to both mark crabs and search for marked carapaces, either dead or alive, could allow for more successful tracking of the crabs’ presence.

Although this year did not have the excitement of recapturing a marked crab, we may have discovered that the crabs do not hang out in the same intertidal for over a week. Our method of marking and revisiting each week indicated none of the same crabs were present in the same location one week later. This could sprout more questions, did the birds eat them? Is the migration a short stint on land? Are these crabs coming to land healthy or weak?

Scientific methods aren’t typically born overnight and sometimes take years to perfect. The crabs are likely to reappear next summer and by then a new crew of technicians and interns will be the brains behind the mark-recapture operation. Maybe they decide to change the marking method or involve electronic trackers to gather more information. It’s possible they keep this year’s methods but make more frequent visits to the site. Either way, they will learn to try and learn, then try again when it comes to working on method development.

This year’s last Jonah crab walk came in late September when our initial group of eight technicians and interns had dwindled to just the four technicians. The crabs had also become more scarce. Over the course of the season, I got to enjoy being a part of the cycle of science that advanced our methods of understanding Jonah crabs. While completing a different intertidal project in the last week of fieldwork I found a Jonah crab nestled deep in a crevice. This crab defies our thinking of when they retreat from the shores, as it was there over a month after our surveys were completed. It was a particularly resilient individual. Holding a crab with the cool air of fall around me I realized that this year’s crab survey was over but the mystery of the Jonah crabs migration was far from being revealed. I foresee years of technicians and interns scrambling over rocks and peering into crevices to find their own Jonahs, and I hope they have just as much fun as I did.