by Olivia Milloway

In late April 2022, Schoodic Institute’s Science Engagement Coordinator Shannon O’Brien led a group of students from Casco Bay High School onto the rocks of Schoodic Point. Situated in a freshwater pool just beyond the reach of the Atlantic Ocean’s salty spray, an observant student spotted a clump of amphibian eggs. Upon closer inspection, Shannon, who has a special love for salamanders, identified them as spotted salamander eggs (Ambystoma maculatum).

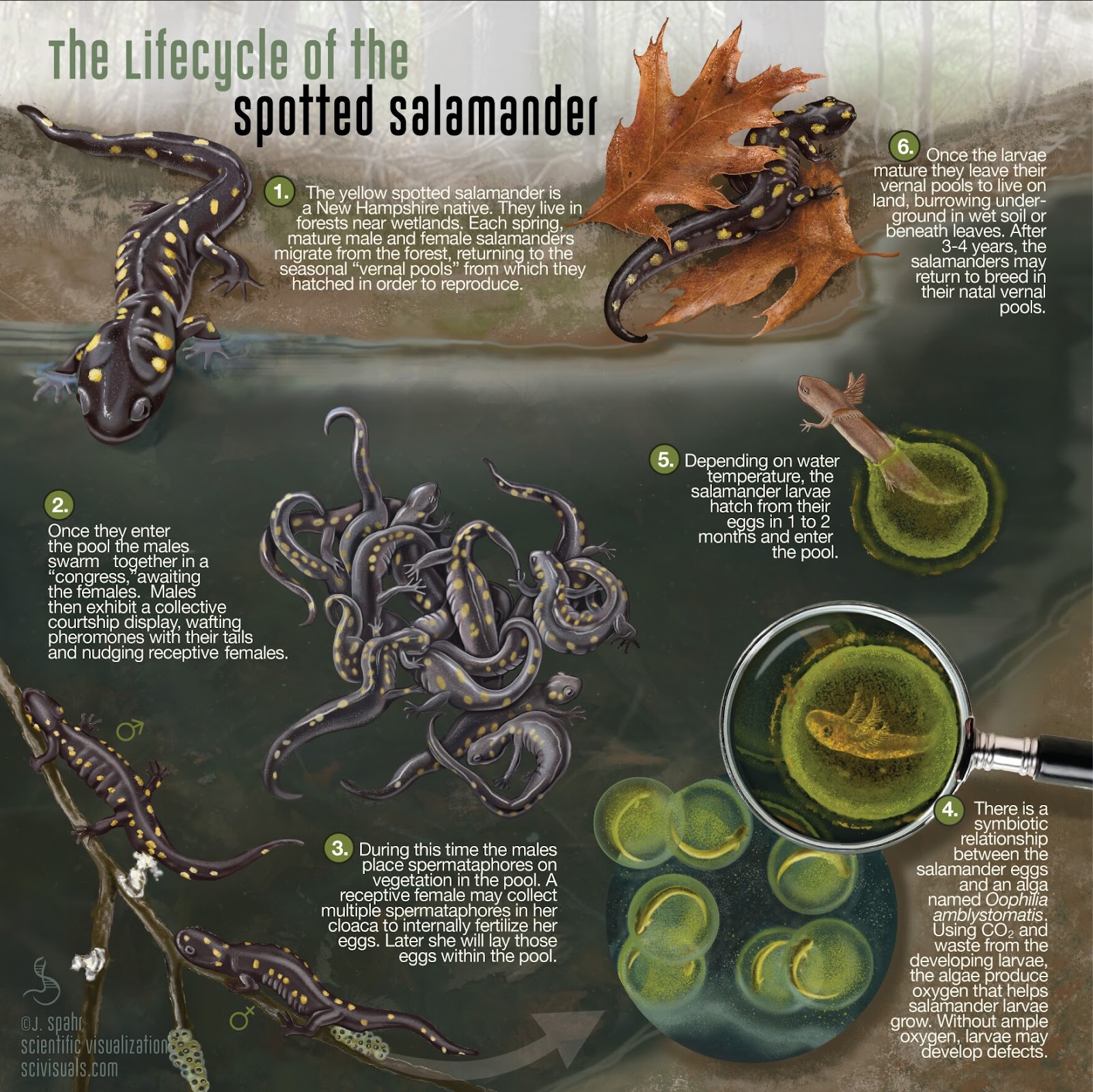

Shannon was a bit surprised that the spotted salamanders had chosen such an exposed site for a nursery, yet nevertheless delighted to see them. Adult spotted salamanders had likely laid the egg masses several weeks prior, migrating in droves under the cover of night to find suitable habitat for their young. In late spring, female spotted salamanders lay their eggs in vernal pools like the ones at Schoodic Point while the males deposit little sacs of sperm called spermatophores that fertilize the eggs. Shannon reported the eggs on iNaturalist and decided to return to the pool to keep an eye on the eggs.

As spotted salamander egg masses develop, the embryos maintain a unique relationship with a species of algae called Oophila amblystomatis. The algae uses the carbon dioxide and waste produced by the growing embryos to create oxygen that in turn helps the embryos grow. This relationship is known as endosymbiosis: two organisms are living together in order to survive, with one living inside the other. Because of this relationship, spotted salamander eggs are often tinged green from the algae.

Shannon later returned to the rocky pool with hopes to spot adults coming to lay more eggs. She chose a warm, rainy night–a night perfect for amphibian activity as amphibians are lethargic during the cold and need moisture to survive. Shannon was shocked to see over fifty individuals in and around the pools. She also ran into Tasman Rosenfeld, an undergraduate researcher at Yale University, who is studying salt tolerance in a population of spotted salamanders at Schoodic Peninsula for his thesis. This work complements that of College of the Atlantic’s Steve Ressel, who is researching a salt-tolerant population of salamanders at Otter Point.

Shannon visited the Schoodic Point pool in mid- June to check on theher baby salamanders and discovered the gelatinous egg sacs deflated and empty. The salamanders had hatched and the larvae were swimming around the bottom of the pool, legless with feathery external gills framing their heads. By the end of the season, the larval salamanders will be big enough to leave the pools and migrate to the uplands to overwinter, emerging next spring to breed like their parents before them.