In the September nor-westers also fly Hawks, sometimes in veritable companies. Evil little sharp-shinned rascals flap and sail through the high air. Eight or ten are sometimes visible at once. Pigeon and Sparrow Hawks in lesser numbers flit south-westward along the mountains of the coast. Great Rough-legged Hawks beat heavily out of the evening woods. Marsh Hawks zig-zag above the swampy meadows; and the Broad-winged Hawks that have been raised in the deepest woods of the Island, whither their fledgeling pipings may lure the young student to a glimpse of their fierce eyes and long yellow legs, now show their broad-banded tails and scream across the spruce-tops. – Charles William Eliot II, “The Summer Birds of the Sieur de Monts National Monument”.

story + images by Seth Benz

Sharp-shinned Hawks continue to ply the autumn skies over Acadia. However, volunteers at our hawk-watching station atop Cadillac Mountain, now in its 28th consecutive season since establishment in 1995, have documented a population decline in Eliot’s “little sharp-shinned rascals.”

Our analysis of historical data for the Landscape of Change project found that Sharp-shinned Hawks were considered “common” in the 1880s and are “uncommon” today – categories that were not different enough for us to include Sharp-shinned Hawks among the “declining” species.

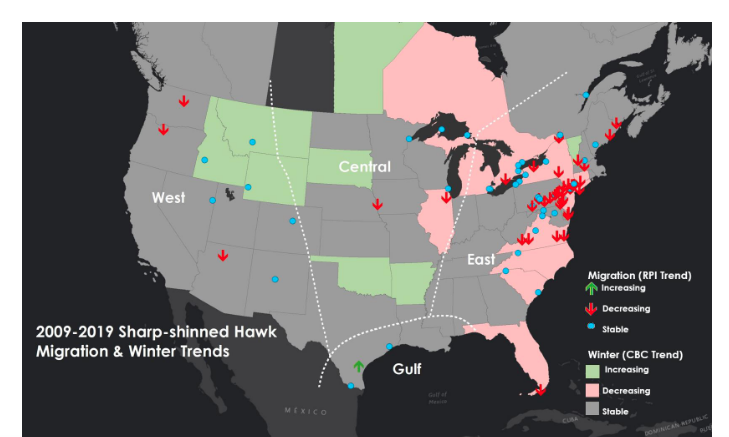

But expanding the comparison beyond Mount Desert Island, with data from the Hawk Migration Association of North America, tells a fuller story.

Among all monitoring sites for North American raptors, more showed declining numbers of Sharp-shinned Hawks during the last decade than any other species, with nearly half of 76 sites continent-wide showing declines from 2009-2019. Eastern sites show a slightly higher decline.

Threats to the species include loss of mixed-conifer forested habitat, diminishing prey (songbird) abundance, pesticides and other chemicals, and West Nile Virus, a mosquito-borne vector that can fatally impact a bird’s nervous system.