story by Kyle Lima

It’s a sunny day, and after being cooped up all winter you decide to get outside for a walk in Acadia National Park. You decide to walk at Seawall where you find yourself along an open field, and happen to notice some small, brown birds in the alders along the field edge. At this time of year, there’s a good chance these seemingly nondescript shrub-dwellers are American tree sparrows, a unique winter visitor that breeds in the tundra across Alaska and northern Canada.

American tree sparrows are one of 14 species of sparrows that can be seen here in Acadia National Park. Almost all of them are small, brownish, and hide in dense shrubs and thickets or spend a lot of time on the ground wearing camouflaged plumages. They can be tricky to tell apart, however the more time you spend looking at sparrows the more you’ll notice patterns like a white ring around the eye (vesper sparrow), alternating black and white streaks on the top of the head (white-throated sparrow, white-crowned sparrow), or bold streaking on the chest and belly (savannah sparrow, song sparrow, etc). Once you get to know the sparrows of Acadia, you’ll find that they are each very different and each strikingly beautiful.

The American tree sparrow is truly stunning and a pleasant warm sight in the bleakness of winter, and rarely do you find just one, as they form small flocks during the winter. The first thing you’ll likely notice is a dark spot right in the middle of their chest, similar to a swamp sparrow. If you observe one through binoculars, you’ll be able to appreciate the rusty color on the head and back that contrasts nicely with the stark gray of the face and white of the belly. If you look closer, you might even notice that the beak is two different colors: black on top and yellow below. If you’re lucky, you might even get to hear one vocalize.

This remarkable sparrow has been seen on every Schoodic Point Christmas Bird Count, having arrived from the Arctic tundra in fall after they have reared their young. In our recent study of Acadia winter birds, we found that this species has decreased drastically since 1970. According to the National Audubon Society’s Survival by Degrees, in every climate warming scenario, the American tree sparrow is at serious risk of population decline, as its Arctic breeding habitat shrinks.

Using eBird and iNaturalist or getting involved in other citizen science projects like the Christmas Bird Count are great ways to help researchers understand how bird populations are changing. You can also get involved with the National Audubon Society and Birds Canada because bird conservation requires teamwork across country borders.

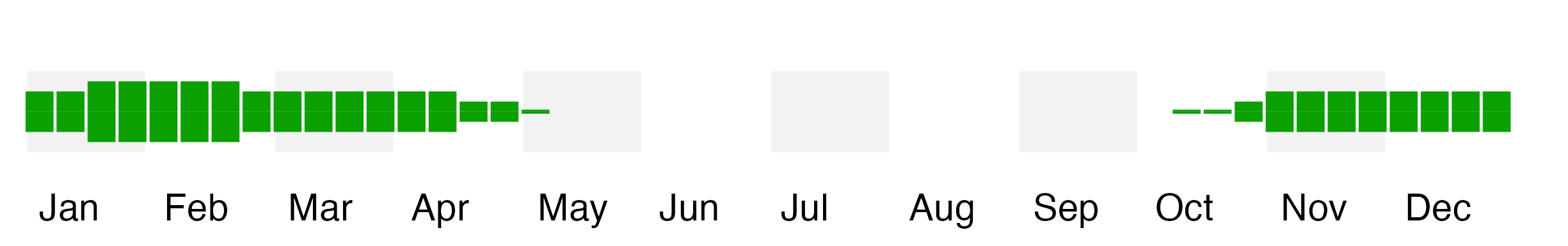

Late January and early February is the best time to find the American Tree Sparrow, but they can still be seen for about another month, so keep your binoculars handy! Check out eBird’s range map to see where others have seen this species.

Header image by Fyn Kynd