by Marisa Monroe, Acadia Science Fellow

I held my phone up to a silent forest, a tangle of black spruce, balsam fir, and sphagnum moss on the southwestern edge of Acadia National Park, still covered in snow. It was March 18, 2024, and although it had not been a brutally cold winter, everything appeared dormant still. Except that.

Hear it?

Peep. Peep. Peep.

My first spring peeper. I recorded the faint wisp of sound as it got carried off in the wind.

Just like the maple sap that flows in late winter, the call of the peeper signals the end of life underground, under snow, under blankets.

That same week, I trained local volunteers to identify the thirteen species of amphibians in Acadia. Our goal was to record the presence of amphibians on park roads from spring through late fall. Everyone was amped up, full of memories of frogs calling, salamanders in basements, the sound of a vernal pool.

There’s a pool in my backyard, was a constant refrain.

The presence of frogs, I realized, is just as important to us as the singing of warblers in spring or the migrations of geese in the fall. Frogs attune our deepest senses to the passing of time. They evoke salient memories of cold, rainy nights in April when the air smells alive; the humid walks in July past the plucking twangs of green frogs; attentive pauses near a patch of woods, listening for the delightful trills of grey treefrogs, hidden on their perches in the verdant August forest. For me, I know it is truly late summer when my trail runs around Caribou Bog plow up waves of leopard froglets hopping at my feet.

To get to the breeding pool, wetland, or stream, amphibians cross roads. And while perfectly adapted to a life without roads, they are frustratingly ignorant of roadway danger. Oblivious to our hectic need to get somewhere, amphibians can be painfully slow.

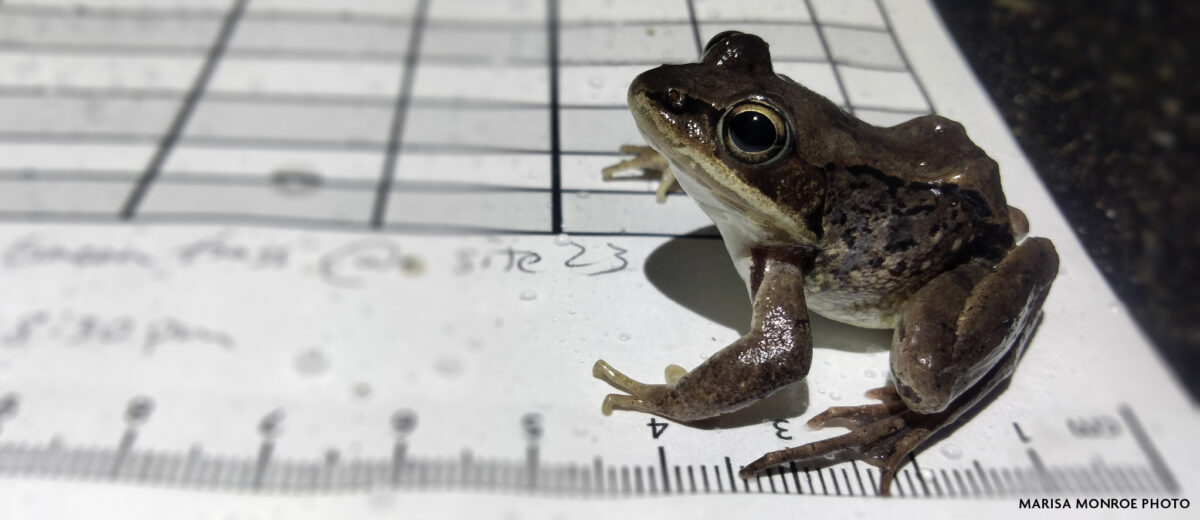

In repayment for what frogs offer us, we look for them, help them cross to safety, and stay up well past our bedtimes. We count and measure. And if we can predict their movements, we can begin to offer more: close a road, build a tunnel, drive the long way around.

After nine months of monitoring frogs and salamanders on park roads with the help of volunteers, we are beginning to see patterns – what species move when and where and when do juveniles leave their pools to join the rest of the population in the forest. The earliest movement was on March 27, 2024, about what we expected, while the latest on November 22 was a thrilling surprise. We can begin to pick apart the variables that might give us the tools to forecast amphibian movements, such as temperature, day of the year, recent rainfall, and the number of previous days without rain. Hopefully, if we can forecast the weather, we can also forecast frogs.

I have yet to hear a peeper this year, but trainings have begun. My volunteers are anxious to start again. How will the timing of movements differ this year from last? I doled out safety vests and we reviewed amphibian identification. I attempted to drive reflective wooden stakes into the ground, markers of where this year’s monitoring sites will be, but the ground was frozen. Amazingly, the frogs, unable to migrate south with the flycatchers and orioles, have remained in this frozen ground for months. The wood frog, when faced with the threat of frost, raises its levels of blood glucose, which acts as an antifreeze within its cells. The toad on the other hand, digs down, and continues to dig as the frost line deepens in mid-winter.

The frogs have been outside our windows all along, yet their seasonal appearance feels like a relief, as if we don’t quite believe that they will be back.

The best way to know frogs after all, is on foot, standing next to a wetland and under stars, letting them sing to us about the seasons.