An update on the Cadillac Mountain Summit Restoration effort

story + photos by Catherine Schmitt

Over the centuries, the highest point along the eastern coastline of the United States has felt the feet of tens of millions: visitors seeking an awe-inspiring view; anxious sunrise-watchers shuffling about in the pre-dawn dark; families seeking a shortcut back to the parking lot; poets needing an empty ledge to lean upon; photographers framing the perfect shot. Most of them are looking east and south, out to the horizon and up to the sky. As they roam across bedrock, they do not seem to notice the clumps of low-growing plants beneath and between their feet.

These are not typical plants, greeting the first rays of light breaking through the fog 1,500 feet above Frenchman Bay. They are unique cohorts of sub-alpine species that have evolved to weather the variable and extreme climate conditions on the summit. The plants themselves are tough, but their situation is fragile, relying on a thin layer of organic matter between granite and air.

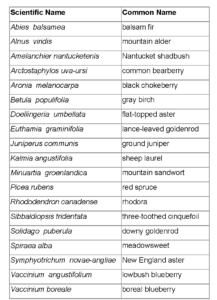

The summit includes a diverse community of 145 different kinds of plants. Grasses, as well as ferns, sedges, mosses, and colorful lichens, grow in the more exposed spots. Larger plants, such as downy goldenrod, New England aster, green alder, gray birch, and balsam fir, find shelter from the wind in the lee of granite ledges. Some species, such as mountain firmoss, boreal blueberry, and Nantucket shadbush, are able to thrive in the tough conditions on Cadillac and are found in few other places within the park.

Over the centuries, all those tens of millions of human feet dislodged root from soil and soil from rock. Wind and water did the rest, eroding away an estimated 16 percent of vegetated areas on the top of Cadillac Mountain to bare rock.

The National Park Service, while wanting to allow people to fully experience the Cadillac summit, for the last few decades have been trying to address the problem. The damage has slowed, thanks to visitors adhering to Leave No Trace principles. Managers also tried roping off areas—some for as long as 25 years—in the hopes that plants would return on their own, but soil-forming lichen and moss work on timescales spanning centuries and longer; without soil, plants could not set down roots. More help was needed to restore the sub-alpine habitat.

This summer, crews of staff and volunteers from the National Park Service, Schoodic Institute, Native Plant Trust, and Friends of Acadia will return to the summit to plant thousands of seedlings grown from Cadillac Mountain seeds into a new six-inch layer of local, sterilized loam—a method that experiments in 2017-2019 showed to be the most successful.

“We know we can’t just add seed to bare ground. We need soil and we need to protect that soil from erosion. We need to be strategic about planting the ideal species,” said Jill Weber, the lead botanist working on the project.

Species that quickly establish include green alder and three-toothed cinquefoil, a stoloniferous plant that spreads across the surface.

“Three-toothed cinquefoil arrives as a seedling or a fragment from a nearby plant, and mixes with grasses, lichens, and mosses to form a turf that stabilizes the soil and provides habitat for other species to grow,” said Peter Nelson, Schoodic Institute Forest Ecology Director. “That’s one of its roles.”

Restoring sub-alpine vegetation at one of the most popular national park destinations in the United States would be a challenge in any decade. But the rapidly changing climate further complicates the effort. Trying to get plants to re-establish in 2021 is made more difficult by heavier rain and ice storms, but also hotter and drier summer conditions.

“I describe what we are doing as setting the stage,” said Nick Fisichelli, Schoodic Institute President & CEO, who has been working on the Cadillac Restoration since 2017. “We want to put back the key set pieces that will allow nature to do the rest, re-organizing and self-sorting, getting on with the show. Can we use seeds grown from existing Cadillac plants? Or should we think about bringing in plants from farther away adapted to warmer temperatures?”

To answer these questions, Fisichelli is working with the National Park Service and Chris Nadeau, a 2017 Second Century Stewardship Fellow and Smith Conservation Fellow, to evaluate whether summit plants are adapted to local conditions. Over the next few weeks, Nadeau will be collecting three-toothed cinquefoil from summits around the Northeast and transplanting them to the test bed on Cadillac Mountain.

“Chris’s work, along with our tree test bed studies, will help us understand how to set the stage for likely success,” said Fisichelli.

Plants hold the script to surviving extreme conditions. “Selecting the right plants is important, because without them, damaging invasive plants that don’t support the native biodiversity of birds and insects on Cadillac Mountain, are likely to move in,” noted Jesse Wheeler, vegetation biologist with Acadia National Park.

“If we are going to invest in restoration, we want to make sure what we do will still be effective in five, ten, fifty years as conditions continue to change,” said Acadia National Park science coordinator Abe Miller-Rushing.

The team working on Cadillac summit this season is bringing the science to this challenge—and helping nature get on with its spectacular show.