story and photos by Elizabeth Halasz, 2021 Intern from University of Richmond

Whether you have a formal background in the sciences or not, you probably have an idea of what a scientist looks like in your head. Maybe it’s media representation of a lone genius who dedicates their whole life to answering an incomprehensibly complex question, or maybe it’s closer to my vision of my biology professors who split their time between teaching classes and running genetics research labs. In any case, these perceptions oversimplify a massive and diverse career field. I’m guilty of believing in this oversimplified and distant idea of who a scientist is, and even after three years of studying environmental science at the undergraduate level and a summer field research internship with Schoodic Institute, I still struggle to include myself in the group of people who do science.

I grew up 30 minutes from Congaree National Park, spent my summers on North Carolina beaches, and “helped” my dad around our garden (which usually meant looking for frogs), so it seemed a natural progression for me to study environmental studies and geography in college. Even so, because most of my scientific exploration has been informal and because I chose to steer clear of chemistry and microbiology classes, I didn’t fully identify as an “early career scientist.”

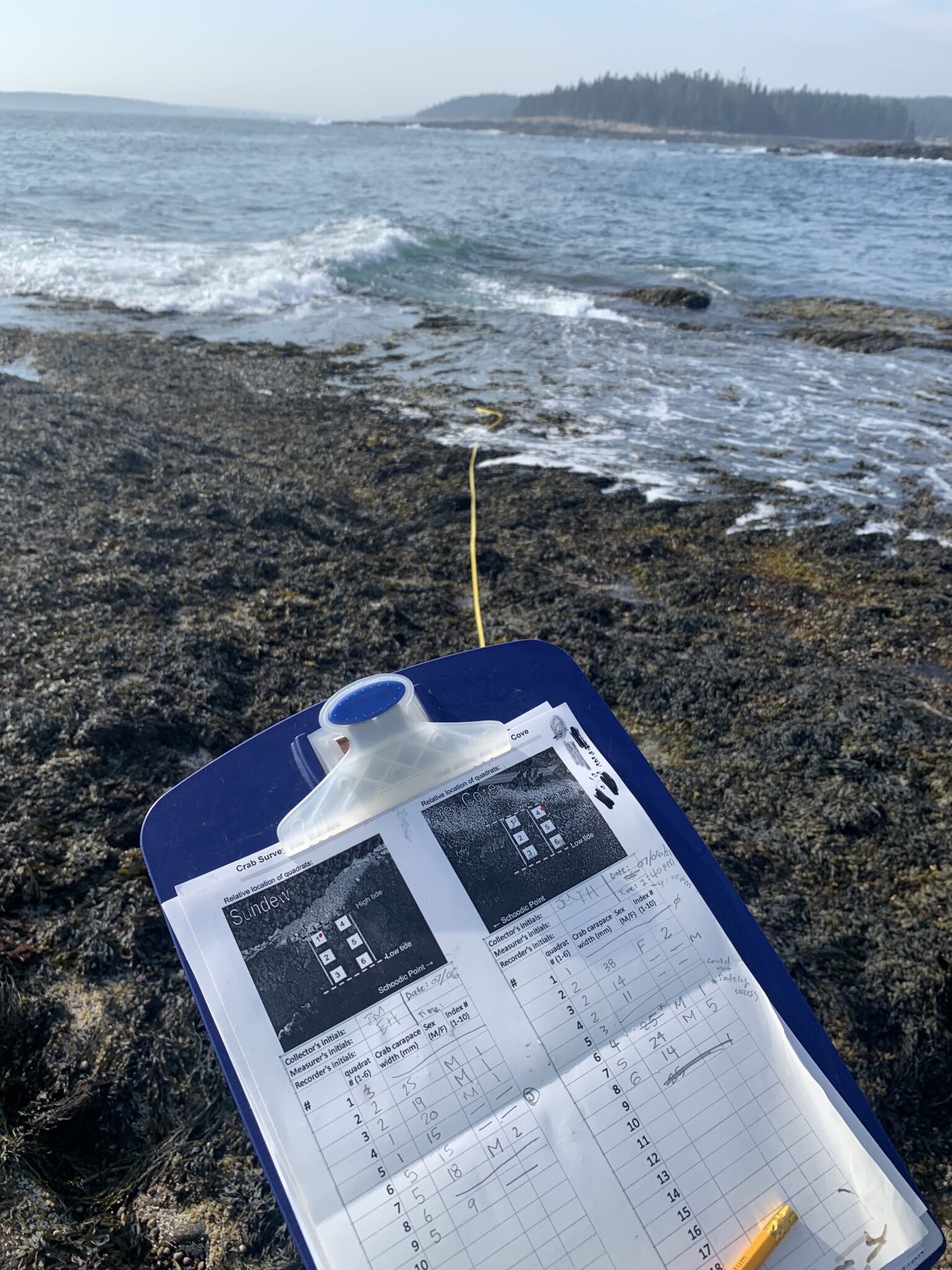

But how else would one describe the interns and technicians working at Schoodic and other research institutions, besides early career scientists? This summer has challenged my previous assumptions about what “real science” looks like. For some, it may be spending long hours in a lab looking at bacteria under a microscope, but for me, “real science” is filled with unexpected challenges and hilarious circumstances. Walking headfirst into an alder shrub during data collection, losing a boot in the clam flats, and filling a Trader Joe’s Just Mango Slices bag with otter feces were just as much a part of my internship as writing research permits, surveying Jonah and green crabs in the intertidal, and replanting native vegetation on the top of Cadillac Mountain.

I realize I’ve held onto a very limited definition of what scientific research looked like for a long time. I valued formal classroom and laboratory learning over my informal inquiries, but these informal experiences prepared me for dodging brown-tail moth caterpillars falling from the canopy far better than an ecology textbook ever could have. In my experience, it’s not how much specialized coursework you’ve completed but how much curiosity and flexibility you have that engages you in “good research.” While I am nowhere close to being an expert researcher, here are a few lasting impressions about scientific learning and exploration that I hope to embrace in my future.

First, don’t overestimate the power of tools you already have on hand. I’m guilty of overcomplicating field protocol simply because I wanted to try out new software and overlooked simpler options. While using highly specialized tools can be exciting, sometimes simple is best and all you need is a data sheet, a phone camera, and plastic calipers. I had previously written off apps like iNaturalist and Seek as research tools, since I had only ever used them for personal exploration. However, these apps and the data they collect are used to support scientific research in the field at Schoodic Institute and across the world.

Second, no one expects you to be an expert in everything. I’ll be the first (and certainly not the last) to say I am not a seasoned ecologist. Humbling myself and accepting that I still have a lot to learn has resulted in innumerable learning experiences this summer. Finding myself surrounded by unfamiliar vegetation prompted me to collect 108 iNaturalist observations during my eight-week internship. Not recognizing snail eggs in an intertidal pool led me on a three-hour literary search on dog whelk life cycles. Conducting field work with other seasonal research staff produced countless information exchanges about the landscapes and species we interacted with. Being “good” at science is not dependent on how much you already know, but how much you are willing to learn.

This brings me to my third and arguably most important takeaway from this summer: Find and follow your own curiosity. Leaning into my interests and questions has resulted in a better understanding of my summer research on Jonah crabs and cross system subsides, given me insight on how to conduct relevant fieldwork, and naturally, led me to even more questions about the ecosystems around me. I plan to continue listening to my curiosity in my final year of undergrad and use the lessons I have learned this summer to influence my future educational endeavors and career in the sciences.