story + photos by Shannon O’Brien

Come September, the spittlebugs have disappeared from roadsides; the deer have grown velvety antlers and the air is chilly with signs of fall. Living and working on campus at Schoodic Institute has allowed me the opportunity to watch the landscape shift with the seasons as life cycles progress.

For example, throughout the summer, while doing fieldwork in the mornings, I would often spot birds catching crabs and dropping them on the rocky shore to crack them before swooping in for a meal. One unexpected seasonal change was the presence of Jonah crabs (Cancer borealis) speckled along the intertidal beds of seaweed starting in August. They could be seen nestled under rocks hiding from the gulls as well as under seaweed or in tidepools.

Coastal Maine has a variety of crabs, from the local rock crab (Cancer irroratus) to the invasive European green crab (Carcinus maenas) as well as the Asian shore crab (Hemigrapsus sanguineus). The native rock crab and Jonah Crab are often grouped as red crabs and harvested together to provide the meat for Maine’s famous crab rolls and other shore-based dishes. Although very similar to its cousin the rock crab, the Jonah is larger, redder, with black-tipped claws. It is usually found farther offshore.

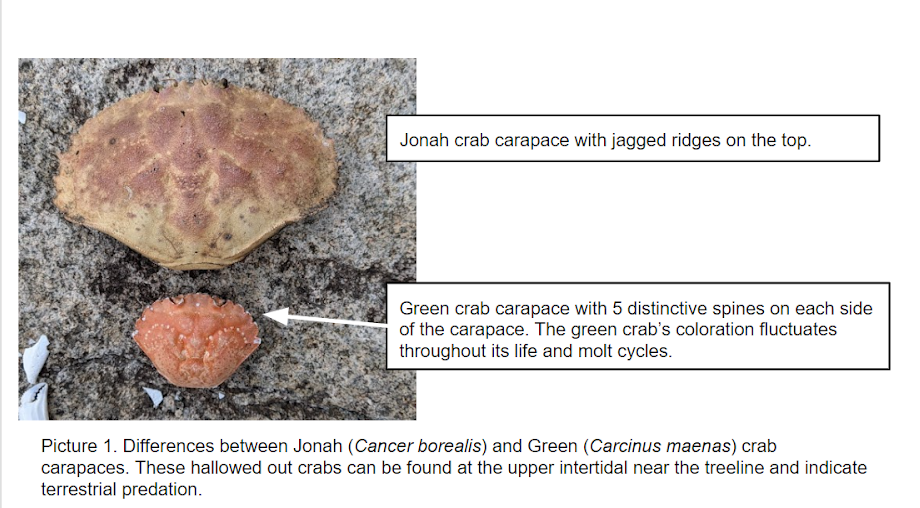

Although all crabs are crustaceans, the appearance of crab carapaces can vary, the green crab has distinctive spines on their carapace compared to Jonah’s more jagged carapace. (Picture 1). The crab community of Maine is diverse and there are some holes in the body of knowledge surrounding the Jonah crab’s life cycle and seasonal habits.

According to New Hampshire Public Radio, the Jonah crab is a growing component of southern New England fisheries, as the lobster habitat range shifts northward due to water temperature increases. Lobstermen and women have started to target the by-catch crab to supplement lobster in a changing world. With the popularity of red crab meat growing, there are also concerns about managing the stock. In order to properly do this there needs to be a greater understanding of the Jonah crab’s current status and life cycle to ensure appropriate regulations are implemented to allow for a healthy Jonah crab population.

This isn’t exclusive to Maine. As a Florida native, I know a commercial stone crab crew and asked about their industry knowledge of the Jonah crab. Beth Nichols of Nichols Seafood Suppliers of Islamorada, Florida said they encounter Jonah crabs and often see people trying to sell them off as stone crabs. Although they are cousins, the Jonah is not a stone crab. Stone crabs are typically larger and often get all the headlines and roadside advertisements as the best crab meat sold at various restaurants and roadside stands in Florida. Stone crabs are considered to be a sustainably harvestable fishery because only the crab claws are harvested, the crabs are returned to the water, where they begin to regenerate their claws. There are still regulations on harvest sizes, season to harvest and egg bearing females, but overall it is a uniquely harvested animal.

The presence of Jonah crab along the entire East Coast indicates a widespread resource that should be allocated more research funding to fully understand the impacts of harvest methods and the crab’s life cycle. There are some existing laws surrounding Jonah crab harvesting in Maine that have similar regulations such as harvesting limits, size restrictions and egg-bearing female harvest bans. The difference is in the knowledge base that has made the law. How long does it take a Jonah crab to regenerate a claw? Do they have a migration (like the one we observed when they come to shore at Schoodic) that leaves them more vulnerable? Should there be a time restricted season? These are science-based questions that can help inform regulations to protect crabs so that a healthy population can persist.

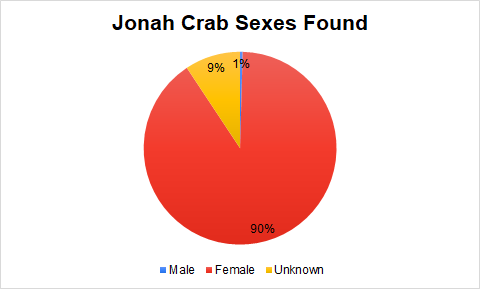

Seasonal changes of the Jonah crab are a particularly interesting aspect to be unfolded. They live along the offshore ocean floor up to 2,000 feet deep, but in late summer we find the crab washing up in the intertidal zone, and a large majority are female (199 in 200 crabs found were female). Lack of knowledge in this spatial movement is concerning as it isn’t fully understood just what the Jonahs’ habits are. As these crabs come ashore they also link into the terrestrial environment, which gives even more incentive to uncover just why the summer migration to shore exists.

On land, there’s a predator-prey aspect to be considered between birds and crabs. With the Jonah crab being found on the shore for a few months a year, I would like to investigate the relationship between the seasonal presence of crabs and immature gulls’ diet. I observed the crabs appearing just as immature gulls started to hunt for themselves. Small enough crabs without proper hiding spots made for easy targets for young gulls to exploit. One can easily interact with the carapace of a Jonah crab by walking along the upper part of a rocky shore looking for hollowed out crab shells, an indication of a shore bird’s recent meal.

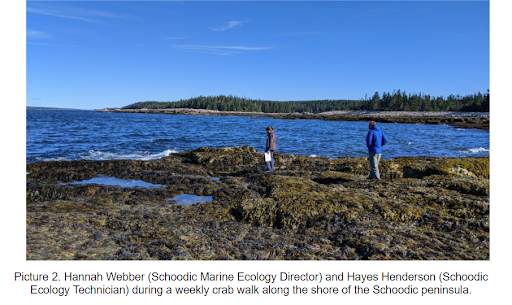

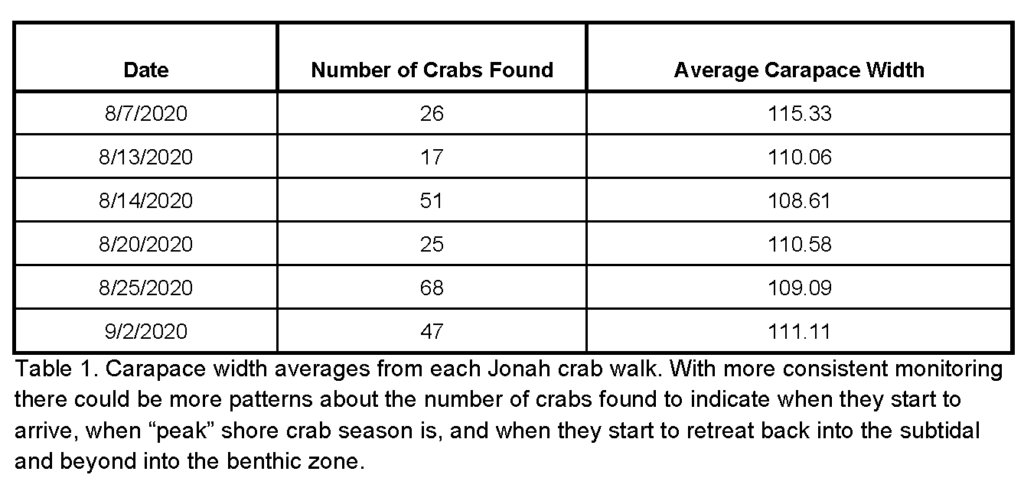

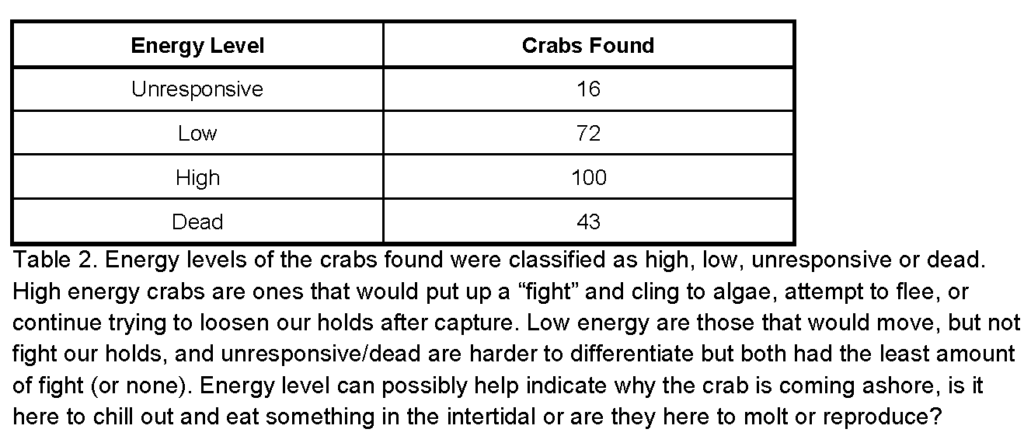

This past summer, we made it a point to do weekly crab walks to search the intertidal zone at low tide for crabs, take measurements and notes, and then return the crab to the seaweed beds (Picture 2 , Picture 3). Data collected included carapace width, sex, whether all legs were present, whether both claws were present, energy level, apparent lesions, and any other notable observations. Some odd observations to date have been the presence of black spots on the carapaces of the crabs, the fact that they occasionally produce bubbles and that almost every crab encountered has been a female.

A curious sight in the intertidal is a crab covered in bubbles. It is thought that this behavior is the result of crabs breathing air on land and has to do with their keeping oxygen going to their gills:

Other questions that remain to be solved are whether there exists a size class that is too big for bird predation, what size would that be, and why do they come ashore in the summer? Below is a summarization of this summer’s findings using visual graphics of the data.

Initial findings of six crab walks done along the same distance and location of shoreline:

Although my job at Schoodic was seasonal, I will carry these observations and information with me into the future as I consider the importance of scientific information to help inform management in order to shape a future of sustainable fisheries in Maine.