by Bill Zoellick and Sarah Hooper

Over the past weeks, we have been looking for a good time to retrieve the Beal Boxes that Mike Pinkham, the Gouldsboro shellfish warden, set out on two different clam flats last spring. A Beal Box is a flat wooden box, 2 feet long by 1 foot wide by about 3 inches deep, covered with heavy-duty window screening (“Pet Screen”) on its two flat sides. It is called a “Beal Box” because Dr. Brian Beal of the Downeast Institute (DEI) has been using such boxes for years to collect data about clam recruitment in different locations all along the coast of Maine. The box is set out on a clam flat around the start of June and retrieved in the fall. Sometimes, thousands of tiny, first-year clams settle into a box over the summer. Sometimes there aren’t any. (But then you usually find a bunch of green crabs that ALSO settled into the boxes and had a great summer eating clams.)

Below is a picture of Lucas, a student from the Sumner Pathways program, opening up a Beal box to begin washing away the mud to find out how many clams are inside. Borrowing from Forest Gump, a Beal Box is like a box of chocolates (but smells different). You never know what you are going to get.

The problem of waiting for a good time was real. We needed the tides to be right so that we could retrieve the boxes in the daylight, and we needed to get them early enough in the day (but not TOO early) so that Sumner Pathways students could help us with the washing, sieving, and counting. We decided that Monday, November 18 would be the day. Low tide was around 8:30 am and the tide would be low enough to allow us to get the boxes.

By last Friday we realized that there was one major flaw in our plan: The weather forecast for November 18 was horrible, with freezing rain and lots of wind. In the past, we have washed the mud off of clams outdoors behind the high school. Also, in the past, our work has been primarily focused on finding clams that measure an inch or more. This time we would be trying to find a lot of tiny clams, sometimes measuring only a couple of millimeters across. There was no way that we could do that successfully outside in the rain and wind.

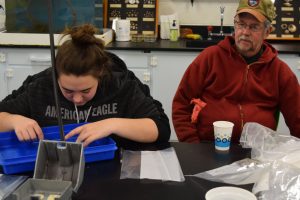

Having great partners is always a good thing, but when you are in a spot like the one we were in on Friday, it is the difference between success and failure. We sent an email off to the folks at DEI to ask them whether we could load the clams into the back of Mike Pinkham’s truck and take them DEI on Great Wass Island so that we could use their new “Marine Sample Processing Laboratory,” a wonderful, indoor and HEATED facility with sinks and hoses that spray filtered seawater to do exactly the kind of work we needed to do. In less than 30 minutes we had the answer back: “We will accommodate your needs.” Wow! Here are a couple of pictures from our work inside the lab. On the left, Alix, Lucas, and Mike Pinkham are using sieves to collect the small clams. On the right, Sarah and Roy are transferring clams from sieve boxes to bags for weighing.

Once we had the clams separated from the mud (and crabs), we used DEI’s classroom facilities to weigh the bags of clams and to weigh and count small samples of clams taken from different bags so that we could come up with an estimate of the overall count of clams.

Once we had estimates of the number of clams and had separated the clams from all of the krill and other small animals that had settled into the Beal Boxes, we put them in a mesh bag that will stay in one of the circulating seawater tanks at DEI until spring. At that time students will retrieve the clams and examine samples to make estimates of mortality. Mike and the shellfish committee will use the clams that survived overwintering as seed clams next year.

Results

This was our first attempt to capture newly hatched clams. We learned a lot of things at different levels of detail. We have already started working with the Sumner students to capture and build on that learning, and we will do more of that later this week and after the Thanksgiving holiday.

Some of the big things that we learned include:

-

The “Deep Cove” site, which is at the northern tip of the Paul Bunyan subdivision in Gouldsboro near Point Francis, does not appear to be a good site for capturing clam seed because there are too many green crabs. (Interestingly, this is also where the middle school students are doing crab research. It seems like the right place!) In June, some crabs are still small enough to fit through the screens on the boxes, which puts them in a position to eat a lot of clams and to grow quickly.

-

The students have not yet done complete, careful calculations from the data they collected, but rough calculations suggest that we captured an average of around 300 clams per box at the site at the top of West Bay.

-

Processing the contents of Beal Boxes is labor-intensive — but there is also probably good potential for us to become more efficient. We are sure the students have some thoughts about how to do that.

It is also clear that there is much more that we need to learn before we can help Gouldsboro learn how to do this work at a larger scale, capturing 100,000 or more clams each year. Over the next months, Sumner Pathways students will work with Mike Pinkham and with the two of us to make a list of the most important questions that we need to answer — and to then figure out how to get those answers. Fortunately, we are not the only group in Maine that is trying to learn how to capture and overwinter small clams. Other schools are working on this problem, as well as conservation organizations, laboratories, and community groups. The Sumner Pathways students will work with Mike, the two of us, and with partners such as scientists at the Department of Marine Resources, the Downeast Institute, and other organizations to connect with and learn from all these other programs.

Yesterday was a big day — a good start. Over the coming weeks and months, we will keep you posted on what the students and the town are doing and learning. Before we close, we want to thank the Sumner Pathways students who worked side-by-side with Mike and the two of us to get this job done and who continue as partners as we reflect on what we learned. We also want to give special thanks to Dr. Brian Beal, Kyle Pepperman, and the rest of the team at the Downeast Institute who bailed us out and made the work possible.

###