by Emma Albee, Science Information Specialist

Every winter, as scientific activity slows in Acadia National Park, I shift my focus from helping researchers apply for permits to archiving and sharing reports from research that has already taken place. Now, as research activity is on hold in order to follow the Maine Governor’s Stay Healthy at Home Mandate, I have had more time to work on the archives.

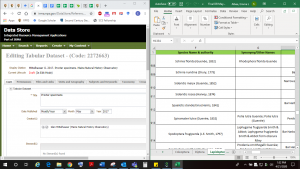

For the past eight years, we have been adding documents about research in Acadia to IRMA, or the Integrated Resource Management Applications, a collection of applications created by the National Park Service to manage and deliver resource information to parks, partners, and the public. One of those applications, the Data Store, is a database of documents and data about natural and cultural resources in parks. Acadia has uploaded more than 3,000 reports to this database.

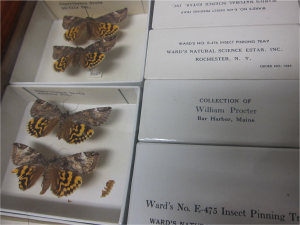

The document I am currently working on is a database of all of the specimens in the Procter collection. This is a collection of species from more than 28 orders of invertebrates that were collected from about 1909-1956 by William Procter and others. These specimens are part of the William Otis Sawtelle Collection at Acadia National Park. It is going to take me about a month to enter the metadata for this database. There were around 100 study locations and more than 7,000 species. The photo here shows just a few specimens of moths from the collection.

Here are some other documents I have recently added to the IRMA Data Store:

- Bass Harbor Head Light Station Historic Structure Report

- Nature-based tourism and climate change risk: Visitors’ perceptions in Mount Desert Island, Maine

- Mercury remediation in wetland sediment using zero-valent iron and granular activated carbon

Staff at Acadia and Schoodic Institute have worked to create a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) on how to upload documents to the database so that there is a common way to do this and the same information is added for each document. This SOP is periodically updated, either when the database is updated, or I learn a better way to enter the metadata. Some of the metadata about the reports is typical for any similar database – title, author, date published. Other metadata is not as typical. In the notes section of each reference, I list any research permits mentioned in the document as well as a list of locations where the study took place. I also add keywords to the document (from a database of more than 800 keywords) plus the higher level taxonomy (class, order, and family) for each species involved in the research. Then, I add a list of the species in the document. These last three parts – study locations, keywords, and species – take the longest to enter. Some documents may not have any of these, some have large lists of all three, and many fall in the middle somewhere. This information is all important, so it is vital to take the time to enter it. For example, when Friends of Acadia, Acadia National Park, and Schoodic Institute were working on the Cromwell Brook watershed as part of Wild Acadia, one part of the project was to look for historical accounts of plants and animals in the watershed to help understand what the watershed looked like in the past. Researchers were able to search the database using several locations in the watershed to come up with a list of documents with helpful information.

An important motivation for this work is to preserve the documents in an archive for the public record. Most documents are uploaded as PDFs to the database, so they can easily be converted to another file format if PDFs ever become obsolete (hopefully that will never happen). The PDFs are also saved onto a hard drive plus a back-up hard drive. Any documents linked to a research permit are printed and added to the research permit folder. All of this is to ensure that the document will be able to be found, via multiple ways, forever.

Archiving historical research, especially information on flora and fauna, can help today’s researchers understand the climate of the past, how conditions have already changed and will continue to change. Once considered dusty relics in warehouse drawers, collections like William Procter’s specimens are now recognized as both relevant and valuable today.