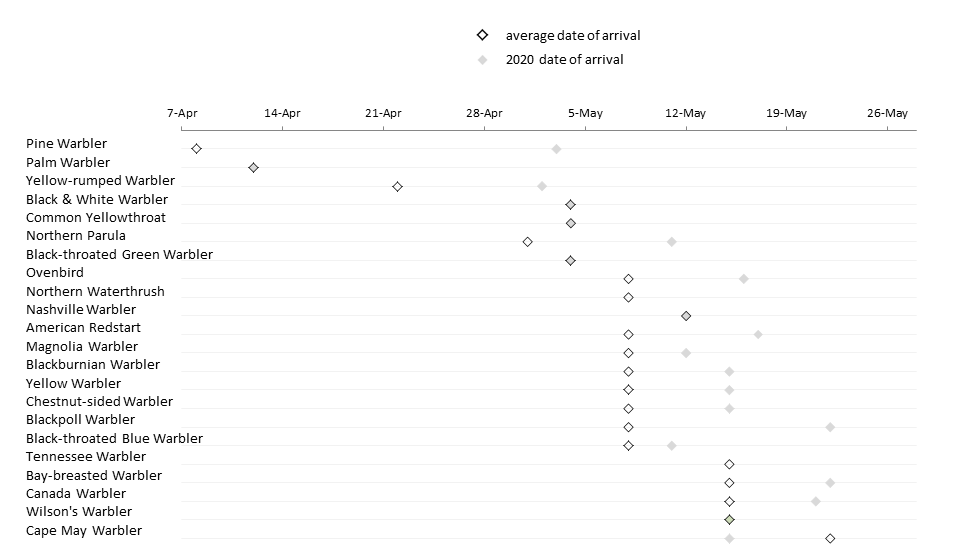

Comparing 2020 warbler arrivals with historic spring arrival dates on the Schoodic Peninsula gleaned from eBird checklists

by Seth Benz, Director of Bird Ecology

Warblers are fascinating. Smaller than sparrows. As colorful as hummingbirds. Melodious songsters. Voracious insectivorous. Migratory celebrities. Historically, the entirety of warbler migration is witnessed from April through May. Some species drop out of migration to nest here, while others continue to travel to breeding areas in the Boreal forest.

Each species is a unique anatomical puzzle of wardrobe patches. In shrubby thickets or among the highest branches of a tall spruce or through a leafy birch tree, their quick flits and darting movements in pursuit of insects expose glimpses of color combinations which the observer must mentally note and hurriedly assemble. Fortunately, some species may sing, giving away their identity and location. Total enjoyment is achieved with a clear view of a whole bird, hearing its song, and then watching its behavior as a known species. All that information can then be transferred into the warbler reference etchings on the mind, a memory to be recalled upon the next glimpse, securing identification before the whole bird all at once appears.

The pursuit of mastering warbler identification cannot be accomplished by sight or sound alone. Becoming familiar with a warbler’s schedule is also a good indicator of what species may be encountered as Spring advances. At Schoodic Institute each Spring, Songbird Watch at Frazer Point documents arrival times using eBird checklists submitted by visiting birders.

Migratory timing is not solely dependent upon distance traveled, though it can be a factor. Migratory readiness is bolstered by the seasonal change in day length (photoperiod), and weather conditions such as precipitation, wind direction, temperature, and frontal boundaries play a huge part in migration dynamics. Clear, starry nights with southwesterly tailwinds are ideal. Heavy precipitation holds up migratory progress. These variables influence the relative timing of each species.

For instance, Pine, Palm, and Yellow-rumped warblers nest here, and commonly winter in the southeastern United States. Dubbed “short-distance migrants,” they typically are the first to arrive in the Schoodic region. Pine Warbler is usually at the head of the migratory parade, occurring as early as the first week of April. Palm Warbler is usually seen during the second week of April, while Yellow-rumped warblers ordinarily arrive during the third week.

This year, however, the first Pine Warbler was not reported until May 3. Therefore, it is referred to as “late” when compared to the historic record. In comparison, true to the status quo, the first detection of Palm Warbler occurred on April 12, exactly “on time”! Yellow-Rumped Warbler was not recorded until May 1, earning a “late” designation.

As each Spring unfolds, a new data chapter in the warbler migration story is entered for each species. Here we must emphasize the need to layer chapter upon chapter, perhaps decade by decade, to begin to render trends in the mosaic of warbler migrations.

The following chart chronicles the arrival date of 22 warbler species on the Schoodic Peninsula during Spring 2020 compared to their historic average week of arrival over the past three decades according to eBird.

It is imperative to note that this Spring’s results have been impacted by fewer observer days on the Schoodic Peninsula due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Another impact was an uptick in precipitation across the eastern United States as warblers were initiating their respective migrations.

The data, archived via eBird, an open-source bird data repository, allow resource managers at Acadia National Park to stay abreast of potential changes within and among warbler and songbird populations.

To help us continue to do this work and contribute to the warbler migration story, we invite you to participate in our bird monitoring endeavors by using eBird any time you visit the Schoodic Peninsula. For more information on how to get involved, please contact sbenz@schoodicinstitute.org.