story and images by Hanae Garrison, 2021 Schoodic Institute Ecology Technician

If you take a walk along the coastline of Schoodic Peninsula or watch the sunset from Schoodic Point, chances are you’ll run into black crowberry (Empetrum nigrum). This evergreen, low, mat-forming woody shrub with distinctive black berries (not the sweet juicy blackberries, but the bitter, tasteless kind) likes to creep out from crevasses in exposed bedrock.

An arctic species, black crowberry resides on Schoodic Peninsula due to its proximity to the ocean, variations in topography and habitats, and a regular diffusion of coastal fog moving inland. Water has a high heat capacity, meaning it heats up and cools off more slowly than land. As a result, areas near the ocean, like the Schoodic Peninsula, take longer to warm and allow cold-adapted species like black crowberry to survive.

Thanks to Schoodic Peninsula’s unique physical characteristics, the area has been identified as a potential climate change refugia. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, refugia are areas that remain relatively buffered from changes in climate over time, sheltering ecosystems and protecting native species from temperature and participation pattern changes. The word “refugia” comes from the word refuge, so I like to think of refugia as safe havens for biodiversity, places where species can take refuge from climate change.

This field season, I worked with fellow Ecology Technician Emily Jackson to develop the Climate Change Refugia project. Our study aimed to determine which locations within the Schoodic District of Acadia National Park are potential refugia for black crowberry.

We wanted to answer the following questions:

- Where is black crowberry found on Schoodic Peninsula (location)?

- How much of it is there (abundance)?

- How is it doing (condition)?

We surveyed several locations within the Schoodic District of Acadia National Park where black crowberry is present. These included areas on both sides of the Schoodic Peninsula and along the coastline on two adjacent islands. We purposely chose to survey some areas sheltered from the open ocean and prevailing winds, and others more exposed to these conditions. Juvenile black crowberry tends to develop in sheltered areas shaded by canopy trees, and then as it matures, it thrives in open heathland (a shrub-dominated habitat) where canopy trees die off. Comparing exposed and sheltered locations can help us understand what makes a suitable habitat for black crowberry at different stages of development.

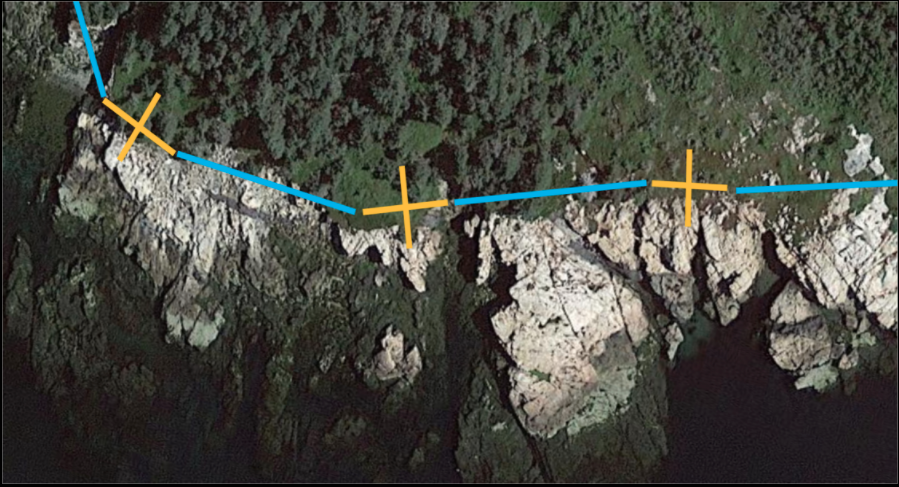

To collect data on the abundance and condition of black crowberry, we walked along sections of the Schoodic Peninsula coastline between Frazer Point and Buck Cove. These areas were absolutely stunning, containing exposed sea cliffs, seaside bluffs, and mountain summits. After admiring the amazing views, we laid down two intersecting five-meter transect lines over patches of black crowberry. One transect line was oriented parallel to the coastline, the other perpendicular. We recorded if black crowberry was present or absent by checking directly under each 10 centimeter mark along the transect line. To determine what condition the patch was in, we noted the percentage of the patch that was alive. We also uploaded a picture of black crowberry with its location and time stamp to iNaturalist for each transect line. We repeated this process every 20 meters, or when black crowberry was observed again.

After comparing the percent cover of black crowberry at each location, we found that black crowberry was most abundant on the adjacent islands of the Schoodic Peninsula. We expected this, as a large portion of these islands consists of exposed bedrock, maritime shrubland, and open heathland, all areas where black crowberry flourishes.

Next, we compared the condition of black crowberry (i.e., the percentage of the black crowberry patch that was alive) at the locations. Both of the adjacent islands had impressive amounts of thriving crowberry with very little die-off. However, both sides of the Schoodic Peninsula experienced more die-off. These sites on the sides of Schoodic Peninsula are close to turnouts off the Schoodic Loop Road, popular locations for tourists to stop and take scenic photos. The die-off seen at these locations could be due to excessive tramping caused by tourists going off-trail to get that perfect shot. So keep that in mind and make sure you stay on the trail or step on exposed bedrock when exploring the park!

Based on abundance and condition, the adjacent islands of Schoodic Peninsula are currently excellent habitats for black crowberry and have a strong potential to operate as refugia in the future. This makes them high-priority sites for continued monitoring and management, as it is crucial to monitor these metrics over time to see how black crowberry reacts to climate change. Hopefully, when future generations visit the Schoodic Peninsula and take a walk along the coastline, they will be able to enjoy the presence of black crowberry just as much as I do now.

If you are interested in learning more about refugia and our results on the abundance and condition of black crowberry on the Schoodic Peninsula, click here to view my poster from the October 2021 Acadia National Park Science Symposium Poster Session.

References

USGS (2020). Climate-Change Refugia Special Issue: Buying Time for Biodiversity to Adapt in a Changing World. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 18(5).

Smetzer, Jennifer and Morelli, Toni Lyn. (2019). Incorporating Climate Change Refugia Into Climate Adaptation in the Acadia National Park Region. Northampton, MA: Smith College.