story by Seth Benz

In the Spring of 1991, I was working as an Audubon warden on an island near Portland, Maine, helping restore a tern nesting colony. Each day’s first task commenced just after dawn, and required climbing up to a lookout platform to take stock of all the birds within sight. Scanning the island’s margin would often reveal a surprising number of North America’s largest duck, the Common Eider. From that vantage point, male eiders appeared roughly white-backed and black-sided. Females, a rich brown color. Both looked robust, reminding me somewhat of a rugby ball on steroids. Each showed a wedge-shaped head with a unique long and sloping bill – a Roman nose of sorts – and a thick neck. No other birds on our watch looked like eiders. They were easy to count, easy to distinguish pairs, and a delight to hear their courting vocalizations of low, hoarse grunts, moans, and croaks.

In the mornings that followed, the number of eiders seen and heard dwindled. I would soon learn that the females were nesting on the island. Meanwhile, the males had moved off in flocks to deeper waters and would have no responsibilities with incubation or chick-rearing. During a nesting survey, we discovered that our island-nesting female eiders chose the cover of waist-high, clothing-tearing brambles in which to hide their nests. The nests were fairly close together, each an oval-to-round shallow depression with a foundation of grass or other plant material and lined with the female’s down feathers. To investigate each nest, we gently lifted a nest-covering blanket of thick, soft, gray down for a quick count of the eggs. Typically, we found four to six, each nearly double the size of a typical chicken egg, and olive-colored. Some hens were so dedicated to incubating the eggs that on several occasions we were able to lift her directly from the nest to be weighed, measured, and banded.

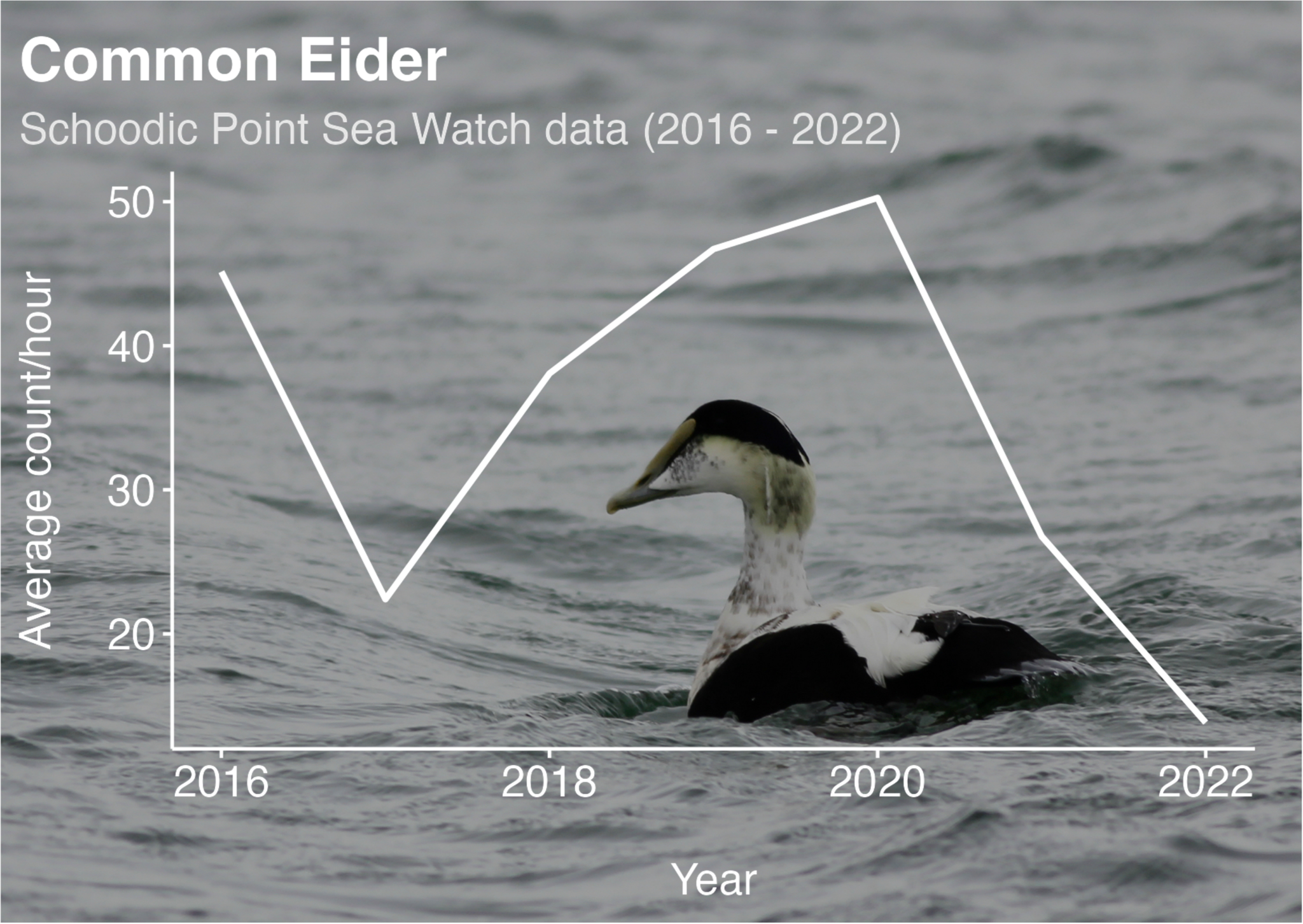

That summer encounter piqued my curiosity about the history of common eiders in Maine. A quick check of contemporary eBird records reveals a fairly steady level of relative abundance every month of the year along the coast of Maine. During fall migration, our season-long Schoodic Point Sea Watch records an average of 9,600 migrating eiders on the move from September into November, though last year’s count was well below average with just 2,579. A recently published Christmas Bird Count report for the past 50 years reveals an undulating pattern of early winter eider numbers, with an overall declining population trend.

Earliest reports on the species status for the northern New England coast described eiders (or “sea ducks”) as common and abundant. However, continuous collecting of the large, nutritious eggs, market hunting for meat, and encroachment for gathering down feathers rendered the population to just a few individual pairs by the end of the nineteenth century. The Champlain Society did not record even one in all of their travels along the Maine coast in the 1880s.

In 1895, Ora Knight reported finding four common eider nests with eggs and wrote in The Auk, “The captain of the boat which conveyed me to the islands informed me that the fishermen considered the eggs a great delicacy, and collected them for cooking purposes. He also informed me that the Sea Ducks as he called them, used to nest in much greater numbers near Isle au Haut, but that the constant persecutions of the fishermen had lately caused the birds to nest on the ledges in greatly reduced numbers.”

In 1904, William Dutcher, reporting for the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) committee on the protection of North American birds, wrote, “The American Eider was formerly a common breeder on the Maine coast but is yearly becoming more rare… Unless a law is passed making a closed season for a term of years, this splendid duck is doomed to extinction in this State.”

The state did pass legislation closing eider duck hunting between February and October, at the urging of conservation-minded citizens and bird advocates, and with support from the National Audubon Society, the eider re-established breeding populations in Maine. By 1913, Charles W. Townsend, who had been a member of the Champlain Society as a student, reported at the 31st annual congress of the AOU that, “in Maine they were at one time reduced to a few pairs, but, by enforcement of laws and by reservations watched over by wardens, they are beginning to increase.”

In 1944, Alfred Gross reported, “the Eider is again firmly established as a breeding bird on the coast of Maine.” In the following decades, common eiders regained and retained their “common” status.

By 1999, population estimates reached 29,000 pairs breeding at 320 sites, numbers that hadn’t been seen since before 1850.

However, eiders remained vulnerable. Continued sport hunting, predation of eider ducklings by great black-backed gulls and an increasing number of bald eagles, potential impacts of bioaccumulation of heavy metals, loss and degradation of habitat, commercial harvests of blue mussels (a favorite food of eiders), avian cholera outbreaks, and increasing environmental stressors from a changing climate have reduced population estimates below 1970 levels.

The future does not look much brighter for the eider. According to Audubon scientists, drawing from millions of bird observations and assessments of threats such as rising global temperatures, the future is projected to witness a range shift of eiders mostly out of the continental United States.

Standing recently at Schoodic Point, binoculars up, I gazed out across the pulsing waves and spotted a low-flying line of 10 large ducks evenly spaced, about a bird’s body length between each bird. They were flying directly southwest, seeking more prosperous wintering grounds, I thought to myself. Three were white-backed and black-sided, seven were uniform brown. All had a similar shape and flight style. I saw determined power in their steady wingbeats as the line moved without pause, slipping in and out of sight seemingly through wave crest and trough. All the signs indicated common eider. I chalked this up as a good birding day.

Yet, I wonder, how many future mornings will carry such potential?