Women of Acadia’s Intertidal Zone

story + photos by Catherine Schmitt

On a bright morning in early February, Jordan Chalfant wandered between tide pools at Seawall Beach in Acadia National Park. A bit of wet snow had fallen overnight, but already the rising sun was proving the day would be unseasonably warm. Here and there amid the sea of brown rockweeds, Chalfant stopped, crouched, and peered beneath a barnacle-crusted boulder, or paused to scan the uneven seascape.

What was she looking for?

“Deep pools, which might hold species typically limited to subtidal environments. Any area that looks special, interesting,” she said. Chalfant is working with Glen Mittelhauser of the Maine Natural History Observatory to write a field guide of Acadia’s seaweeds, similar to the Plants of Acadia National Park and Wildflowers of Maine Islands.

Chalfant had already identified and photographed most of the common seaweeds, and had moved on to looking for more unusual specimens.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Chalfant graduated from College of the Atlantic in 2012. Since then, she has spent the winter months collecting, pressing, and working on her seaweed identification skills. She describes herself as “a shameless natural history fanatic, taxidermist, horticulturalist, botany-head, bird-geek, and museum-rat, suffering from the tragic ailment of falling in love with everything that I explore.”

She has monitored seabirds on offshore islands of the Gulf of Maine, tended plants in the campus greenhouse, and created several of the displays in the Dorr Museum of Natural History. She guided tours in Acadia for four years. She is a painter and illustrator. She was a Schoodic Institute Dixon Fellow in 2014. She continues to assist Maine Natural History Observatory and Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge with plant and bird monitoring. She began working with Mittelhauser on the seaweed guide in 2019.

Seaweeds present a challenge even to an experienced naturalist like Chalfant. Unlike plants, marine algae don’t follow the rules of taxonomy. The same species can look totally different depending on where it grows. They are difficult to access, living where they do on slippery rocks and wave-slicked shores exposed on the lowest tides.

There’s hundreds of species of marine macroalgae in Maine, “but we don’t really know,” said Chalfant, who is also interested in how seaweed populations may be shifting. “And to show any change, we have to know how things were in the past,” she said, leaping over a patch of ice-encrusted rockweed.

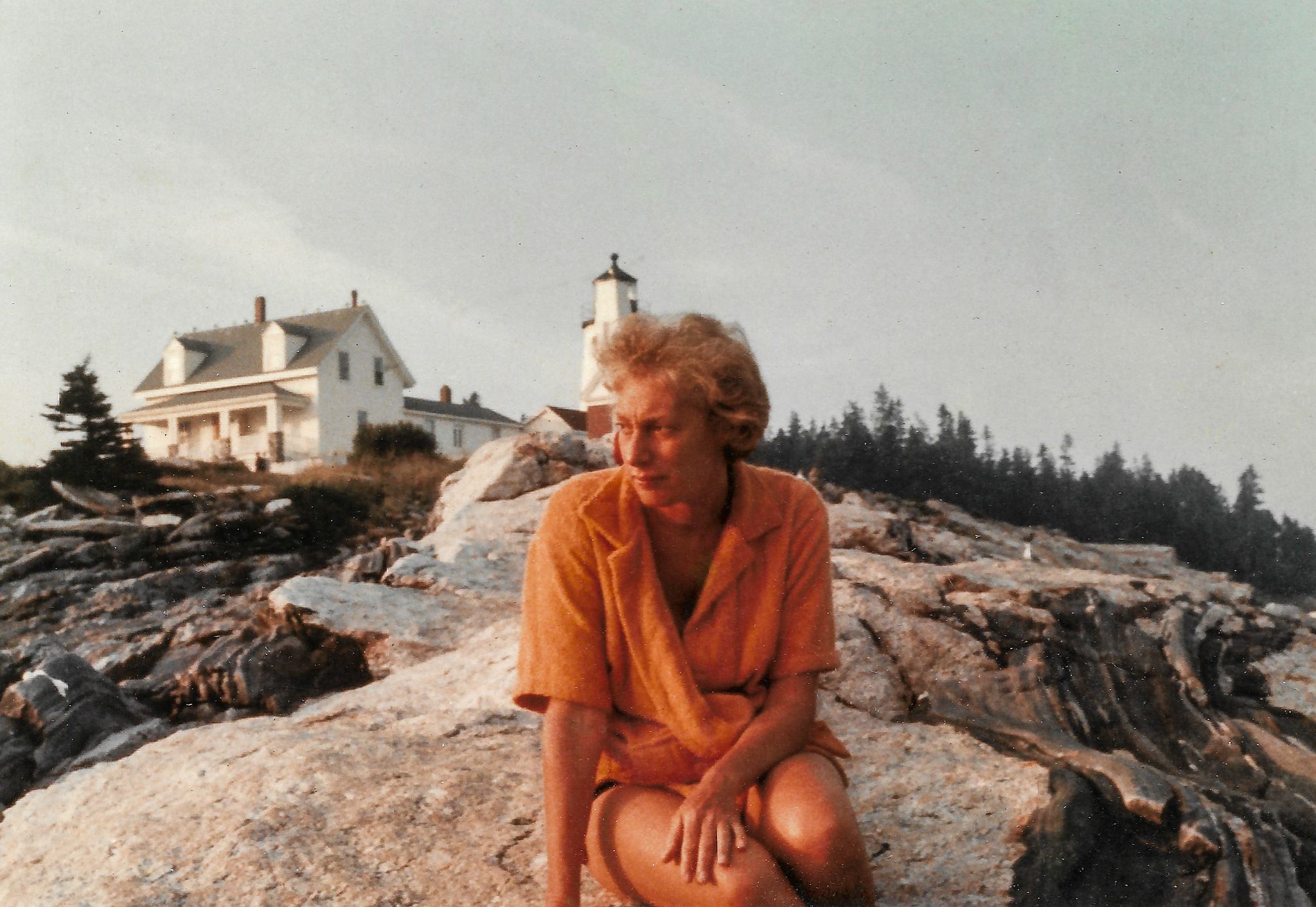

In the 1960s, Denise Van Hemert spent two years studying marine algae in Acadia’s tide pools for her master’s thesis at the University of Maine. Then, with a grant from the Student Conservation Program, she conducted a complete survey of marine macroalgae of Acadia National Park. She took great pleasure in the work.

“The cold, fertile waters and the exposed rocky shores of Maine are very favorable for support of a rich and varied flora,” she reported. She identified 86 species of marine algae. She found the greatest diversity in the most exposed locations, including Seawall and Schoodic.

The historical record is less clear on Van Hemert’s career path. She was a research assistant at Yale in the 1960s, and then an assistant professor of marine ecology at Quinnipiac College. According to her nephew, Thomas Reardon, she led an unconventional life, and loved biology. “She would say that her life really came alive when she retired,” he said. “She pursued art and travel, and never seemed to waste a minute of her time not enjoying her freedom. She loved everything about New England and split her time between her home in Connecticut and her cabin in Vermont.”

Denise Van Hemert died in February 2020 at the age of 96.

In April 2021, Schoodic Institute Marine Ecology Director Hannah Webber initiated a repeat of Van Hemert’s survey, with assistance from Chalfant, Mittelhauser, and Jessica Muhlin of Maine Maritime Academy.

“Repeating Van Hemert’s survey gives us an opportunity to see if and how the intertidal flora may have changed over the last fifty-ish years,” said Webber, “and we are providing future historical ecologists with a glimpse at what intertidal flora looks like in 2021. Acadia has a rich history of scientific investigation. We’re building on that rich history and bringing it forward. Plus, getting into the intertidal with fellow seaweed lovers is an absolute joy.”

“We had a list of what Denise had observed, and we tried to identify as many species as we could,” Muhlin recalled. “We paid attention to the tide, starting low and working our way up.” It was hard, because species names have changed and it wasn’t always clear if they were looking in the same places. But it was fun, too, said Muhlin. “I love seaweed forays, especially with three people as interested in seaweeds as me.”

Muhlin assists in surveying Acadia’s intertidal zone every year with the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Program. She also involves students in the monitoring. “They love being out in the park, and take pride in helping collect information that will be useful,” said Muhlin.

Muhlin was herself a student when she began studying macroalgae at Schoodic as part of doctoral research with Susan Brawley at the University of Maine. Brawley has been conducting research at Schoodic Point for more than thirty years.

“The coast has changed so much, diversity is lower now,” said Brawley. “I think Acadia is starting to change, too.” She has noted that there seem to be less winged kelp and dulse, and more coralline algae. More data will be needed to fully understand the changes.

Which is why it is good that Jordan Chalfant has decided to stay on Mount Desert Island, where she currently manages The Naturalist’s Notebook in Seal Harbor. She told herself after graduating from college that if she stayed, she would keep learning, and give back to the community. Working on the seaweed guide is part of giving back.

In her desire to create a true “field guide,” Chalfant wants to describe the seaweeds based on observational details rather than the microscopic or genetic characteristics that scientists use to confirm identification of species. In this, she finds not having an advanced degree helpful. “I’m more conscious of the learning process. It’s easier for me to describe how to tell different seaweeds apart,” she said. In this, Chalfant is continuing the legacy of Augusta Foote Arnold, author of the first popular guide to the intertidal zone.

“Jordan’s work shows the importance of national parks to science. Parks allow all kinds of scientists, not just those with a Ph.D., to contribute information or understanding,” said Muhlin, who is helping Chalfant identify some of the trickier seaweed species.

Chalfant has documented 73 species of macroalgae so far. She’ll return to Seawall and to other locations in coming months and seasons, to capture the full diversity of seaweed in Acadia.

The tide pools will be there, waiting.