by Catherine Schmitt | cover image by David Manski

This week is National Moth Week. At Schoodic Institute, we’ve been thinking about moths a lot lately, because they are a focus of the Landscape of Change project. As part of this project, we are re-visiting the work of past scientists and naturalists to understand how the environment of Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park is changing.

A key data set in the project was compiled by William Procter, who led a comprehensive survey of Mount Desert Island insects between 1927 and 1950. Of the 1,312 moths he documented, 229 have been seen so far this year in or around Acadia National Park, as reported to iNaturalist.

The moth with the most observations in Acadia and the surrounding region this year is the browntail moth, which was introduced from Europe in the 1890s. Browntail moth caterpillars devour oak leaves and shed hairs that can cause skin rashes and respiratory issues in people, and they have been a particular problem this year. Procter collected a single specimen in July 1935, but reported it as “abundant during 1911-1914, and during 1944.”

Historic information helps scientists working today understand that browntail moth “outbreaks” have happened in the past, and to analyze factors that may influence their population such as precipitation patterns. Of course, this information is not much comfort to those suffering ill effects.

Past records also help identify new species that have arrived in Acadia via range expansions or introductions. During bioblitzes in 2004 and 2011, some 80 species collected during June and July surveys were new to the park, and 20 were new to Maine. According to the final report, new moth introductions from Europe include large yellow underwing, double-lobed moth, small rivulet, and carrot seed moth. “Spotted peppergrass moth, recorded during the July 2011 blitz, is a well-known summer migrant to the southern U.S., but historically it rarely reaches this far north. The extremely long hot spell of 2011 might have played a role in its occurrence in the bioblitz. Scribbled sallow moth was previously recorded reliably in the state only from Kittery Point in extreme southern Maine. Its occurrence in the Park represents a significant northern range extension. The distinctiveness of this species makes it unlikely that the Procter survey would have overlooked it.”

Procter was not the only one collecting moths on Mount Desert Island. He had help from contributors like Charles Johnson and Auburn Brower, and they were building on the work of earlier naturalists.

In the 1880s, a college student named Roland Thaxter collected moths and butterflies on Mount Desert Island. Thaxter, son of Levi Thaxter and Isle of Shoals poet Celia Thaxter, was a member of the Champlain Society, a group of Harvard students who spent their summers camping on Mount Desert Island studying plants, animals, weather, and the environment. (The Champlain Society was the inspiration for the Landscape of Change project.)

Some of the specimens Thaxter collected are archived in the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Others, including caterpillars, are described in the Champlain Society’s journal entries, including this one for August 2, 1880: “R. Thaxter was out walking in the woods in both the morning and afternoon. He got many larvae; among them being 7 specimens of the rare Platysamia columbia…”

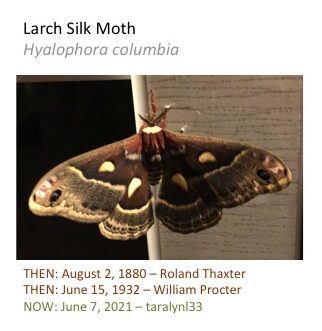

This is the larch silk moth, now known as Hyalophora columbia.

Procter found larch silk moth in Eden (Bar Harbor) on June 15, 1932. He described it as “not common,” but it can still be found on the island today. Naturalist taralyn33 found this species on June 7 in Blue Hill; there are two additional observations from Mount Desert Island in 2018 and 2019.

Like butterflies, bees, birds, and many other creatures, moths are often closely associated with specific plants or habitats. For example, larvae of the larch silk moth feed on larch (or tamarack) needles; and so the presence of this species suggests that tamarack trees and their wetland habitat are also present.

Or how about the primrose moth, Schinia florida–this moth was seen in the Acadia region on July 17, 2021, and on Mount Desert July 17, 2020 – the very same day that Procter found one in Eden! This moth is associated with the evening primrose – it lays its eggs on the plant and can be found resting head-first inside the yellow flowers during the day – and so this wildflower must be common enough to sustain a population of its moth.

Or take the slender or graceful clearwing, Hemaris gracilis, a species considered “vulnerable” in the United States. This moth has wings like windows and hovers like a hummingbird, feeding on the nectar of various flowers, including pickerelweed, blackberry, phlox, and “weeds” like dandelion and hawkweed. The caterpillars feed on blueberry and sheep laurel. I saw it on July 10 of this year near the base of Cadillac Mountain; William Procter saw it on June 2, 1937, in Southwest Harbor, and also noted it from Great Meadow and Witch Hole Pond.

This information can be a source of comfort, reassurance—there are wild things still here, all around us, and surely part of the reason is the conservation of much of the Mount Desert Island landscape. To find again an animal that also lived here 100 or 150 years ago is also inspiration for our work to restore, manage, and protect Acadia now and into the future. Conservation of land and wildlife remains necessary and important, but it is not enough, as pollution and climate know no boundaries. We have to be reminded of why we do this work, and why we need others to join us.

Because, as we evaluate this Landscape of Change, it is just as important to find that some things have not changed—like a burgundy and olive-green fur-covered moth that flies like a bird with wings of glass.