by Catherine Schmitt and Seth Benz

If you are rolling down the boardwalk of the Jesup Path this summer and come upon a cluster of people inspecting trees, examining the ground, chasing dragonflies, watching birds, and photographing mushrooms, you’ve probably run into a “bioblitz.”

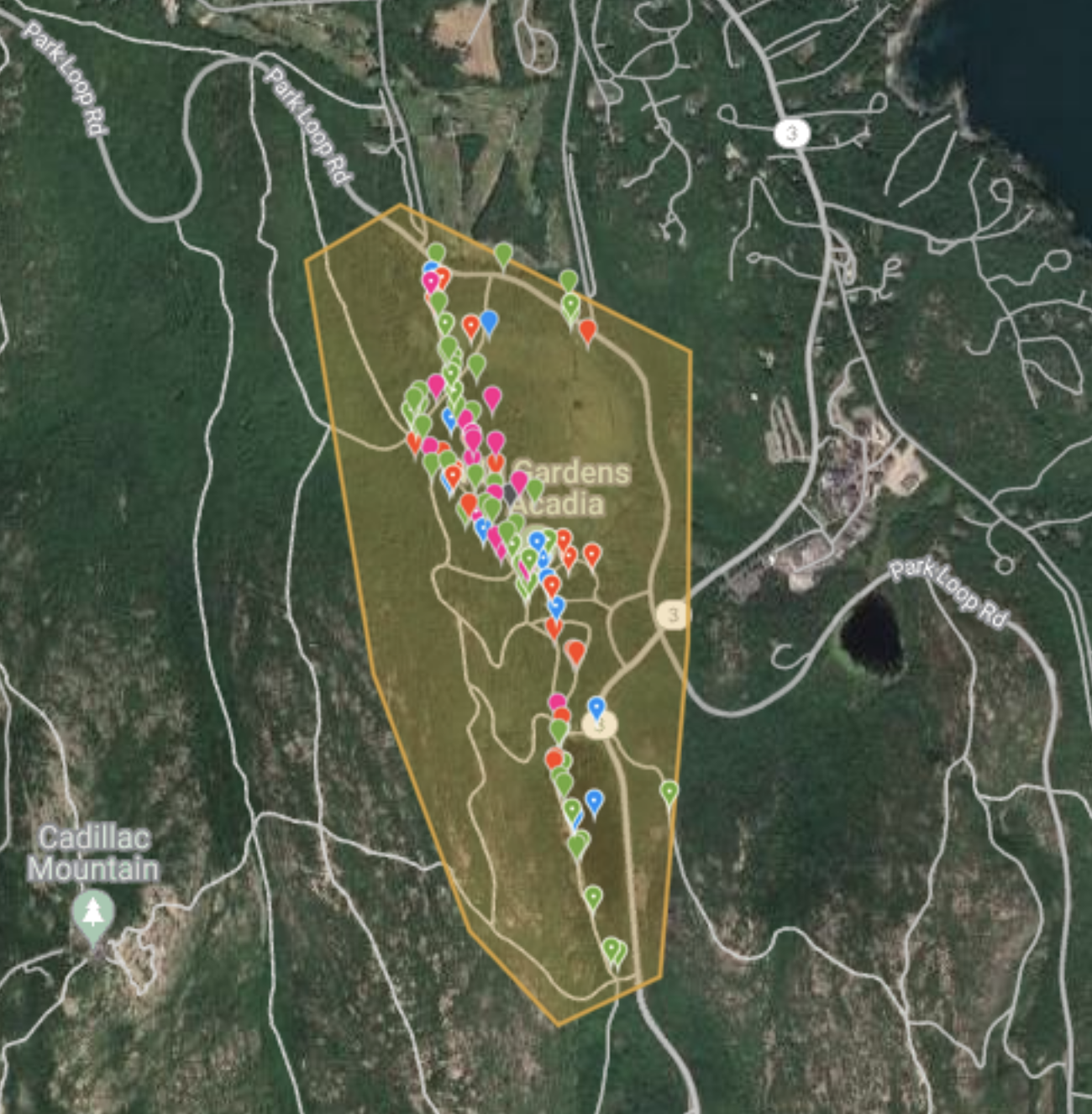

Since 2020, in partnership with Acadia National Park and Friends of Acadia, we have guided more than one hundred people of all ages along the Jesup, Hemlock, and Wild Garden paths to document the diversity of life in the Great Meadow Wetland using iNaturalist. To date, these volunteers have made nearly 3,500 observations of almost 600 species.

Eastern white pine, striped maple, eastern hemlock, and other trees and shrubs lead the list of most observations. These plants are rooted in place and easily seen during all seasons. From the seemingly humble act of photographing a bird, bug, or birch tree, iNaturalist users expand our knowledge and appreciation of nature in and beyond Acadia.

All of the observations help park managers, charged with “protecting the diversity of living organisms,” understand what lives in Acadia where and when. Staff capacity is limited, and by conducting bioblitzes we can increase the number of “eyes and ears” paying attention to nature in the park. By doing so, we join a long legacy of public contributions to knowledge of the region’s flora and fauna. Because Acadia has such a rich archive of historical biodiversity data, observations made today can be compared to past records to understand change over longer time periods, something we are doing with the Landscape of Change project.

In the case of the Great Meadow Wetland, bioblitz participants also help us understand change in an area that is the focus of a major effort to restore water flows, protect trees and other plants, and enhance resilience to a changing climate. Knowing what lives in the Great Meadow now can help us evaluate how the wetland and forest changes after the work is completed, and then as the climate continues to warm.

For example, we want to know about the presence of glossy buckthorn, an aggressive plant introduced to Mount Desert Island for gardens and landscaping, and observed by bioblitz participants on 33 occasions. Despite intensive work to remove the shrub, it continues to appear (this spread is the focus of Second Century Stewardship fellow Nicole Kollars). Tracking locations of the plants aids the park in their work.

Another example has to do with water. As the flows of Cromwell Brook and its tributaries are restored in the wetland, will we see a shift in iNaturalist observations from disturbance-tolerant plants like glossy buckthorn and lake sedge to more wetland-specialist plants?

The Great Meadow Wetland area includes the Tarn, Jesup Path (boardwalk and meadow), and the Hemlock Trail. Participants use their own mobile devices, or tablets we provided, to collect iNaturalist observations. Colby College intern Ben Iannuzzi recently reviewed bioblitz data.

A bioblitz typically involves people associated with a group, such as Earthwatch or Sierra Club, who are participating in other Schoodic Institute programs. But anyone can contribute to our knowledge of the Great Meadow Wetland anytime they visit the area. Outside of bioblitzes, there are many more iNaturalist observations since 2016 by people acting on their own—including myself and my fellow Schoodic Institute staff! Another application we use to monitor biodiversity is eBird. During the same 2020-2022 bioblitz period, 605 observers submitted 1,028 separate checklists of 165 bird species.

Celebrate Citizen Science Month 2023 by joining the iNaturalist community, learning more about past bioblitzes in Acadia, listening to the voices of participants, and subscribing to our monthly newsletter to find out about upcoming citizen science events.